“Alice in Wonderland” continues to inspire readers across the world

( My article on Alice in Wonderland has been published in Hindustan Times popular and widely circulated Sunday  supplement Brunch on 18 October 2015. It is a generous two-page spread in print

supplement Brunch on 18 October 2015. It is a generous two-page spread in print with the title “Curiouser And Curiouser”. I am c&p the text from the digital version here. The original url can be viewed at: http://www.hindustantimes.com/brunch/alice-in-wonderland-continues-to-inspire-readers-across-the-world/story-NKnM2TiOACiTMXQXtUI51M.html )

with the title “Curiouser And Curiouser”. I am c&p the text from the digital version here. The original url can be viewed at: http://www.hindustantimes.com/brunch/alice-in-wonderland-continues-to-inspire-readers-across-the-world/story-NKnM2TiOACiTMXQXtUI51M.html )

Scottish writer George MacDonald persuaded Carroll to self-publish Alice. It had been tested out on the MacDonald children by their mother – and the family loved it. (Above, Carroll with Mrs MacDonald and her children.) (Getty Images/Science Source)

Who’d have thought a self-published story written for the daughters of a friend would become a world classic, eagerly bought, borrowed and downloaded even now, 150 years later?

Start of many things

Alice in Wonderland is about a girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit hole in pursuit of the White Rabbit and discovers a nonsensically delightful world with colourful characters like the Red Queen, the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat and the March Hare. More writers, artists and creators all over the world have credited Alice as an inspiration than any other book, thanks to its imaginative world filled with fantastic linguistic acrobatics in rhyme and prose.

That the book should have emerged in the staid Victorian era of verbose and righteous prose says much for the power of creativity. Carroll was persuaded to publish Alice with his own illustrations, by Scottish author and poet, George MacDonald.

The story had been tested out on the MacDonald children by their mother. The family thoroughly enjoyed the tale, and Carroll self-published it. Then, it was edited and published by Alexander Macmillan.

Lewis Carroll requested the well-known artist of Punch, Sir John Tenniel to create the illustrations, many of which were ultimately based on the original drawings made by the author. To commemorate the 150th year of its publication, Macmillan, the original publisher, has produced a scrumptious edition of The Complete Alice, with the original Tenniel illustrations in full colour. It is unusual for a publisher to be celebrating 150 years of a text, but Alice in Wonderland is perceived to be “a world text”.

Lewis Carroll requested the well-known artist of Punch, Sir John Tenniel to create the illustrations, many of which were ultimately based on the original drawings made by the author. To commemorate the 150th year of its publication, Macmillan, the original publisher, has produced a scrumptious edition of The Complete Alice, with the original Tenniel illustrations in full colour. It is unusual for a publisher to be celebrating 150 years of a text, but Alice in Wonderland is perceived to be “a world text”.

Alice in Wonderland is about a girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit hole in pursuit of the White Rabbit. On the left is an illustration of the character by Carroll himself, and next to it (right) by Tenniel. (Photos: Stapleton Collection/Corbis, The Print Collector/Corbis)

“It’s one of those texts that IS, like Shakespeare,” says graphic novelist Samit Basu. “Its constant reinterpretations in everything, from zombie comics to action-fantasy novels, have kept the original text alive, and that’s the greatest thing that can happen to any book.”

This is evident by the text’s vast influence across creative platforms and genres – storytelling, play on words, visual arts, filmmakers, still photography and translations.

According to filmmaker and author Devashish Makhija, a lot of motifs from Alice have been uncannily replicated across the world. “Tweedledum and Tweedledee seem to have inspired Herge’s Thompson and Thomson in Tintin,” he says. “Batman’s Joker seems to have shades of the Mad Hatter, at least in his inexplicable (but profound) reliance on creating some sort of chaos in anything he communicates.”

And there’s more. When Alice fell down a rabbit hole to discover a topsy-turvy world, Makhija argues, she opened a clear story-telling device for creators of the future. “The ‘hole’ – although in existence before this book – was used pointedly for the first time as a portal connecting two dimensions through which a character ‘travels’.

It has since been used in versions in almost ALL of fantasy writing: the wardrobe in CS Lewis’s Narnia series, the square drawn with chalk in Pan’s Labyrinth, platform 93/4 inHarry Potter, the bridge of Terabithia, HG Wells’s time machine and even the bathtub in Anurag Kashyap’s No Smoking.”

Follow that rabbit

“Every reader will leave with a different reading,” says Anil Menon, author of speculative fiction. “Fortunately, Alice in Wonderland has remained what it was intended to be: an invitation to play.”

Let loose in the imaginative world of Alice’s Wonderland, children often find their own wonderlands when they become adults, says photographer and musician Ed Valfre. “Several years ago, I wrote two children’s books about a boy in the backseat of a car who creates stories from all that he sees on the road. As Alice decides to go down the rabbit hole to discover the fantastical world of Wonderland, my hero goes down a similar path but it is inside his own head. The rabbit I follow is some ordinary thing we see every day. The rabbit hole is our imagination and we simply have to pay attention to discover it.”

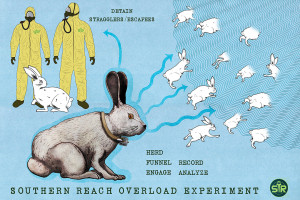

Jeff VanderMeer, who won the Nebula 2014 for his novel, Annihilation, says that Alice “was such an influence. I  started a far-future novel when I was 13 in which a human-sized bio-engineered white rabbit is found murdered at the base of Mount Kilimanjaro. What appealed to me was the surreal aspect of Carroll’s book, even more so than the kind of mathematical logic and the humour. I couldn’t escape Alice even if I tried. It’s one of those constants, or compass points, that for some odd reason draws out originality despite being riffed off again and again.”

started a far-future novel when I was 13 in which a human-sized bio-engineered white rabbit is found murdered at the base of Mount Kilimanjaro. What appealed to me was the surreal aspect of Carroll’s book, even more so than the kind of mathematical logic and the humour. I couldn’t escape Alice even if I tried. It’s one of those constants, or compass points, that for some odd reason draws out originality despite being riffed off again and again.”

There are no white rabbits in filmmaker Paromita Vohra’s work, Unlimited Girls, but Vohra says it is deeply influenced by Alice in Wonderland. In the film, a young woman is drawn into an Internet chat room – kind of like a rabbit hole – and then proceeds on a journey through the world of feminism where she meets all kinds of characters and undergoes all kinds of transformations.

“I think Alice is (like a good Bollywood film, almost) one of those works that gives you permission to make a work out of what you see, what you feel as one,” says Vohra.

In many ways, Alice is a nonsense book. Not in the sense that it is the product of a muddled mind, but because of its willingness to see more in the world than a single outward façade. That’s the aspect that influenced children’s author, known especially for nonsense writing, Anushka Ravishankar the most.

“I remember reading Alice as a child and being fascinated, but also really disturbed because of the strange creatures and the weird, unworldly goings-on,” she says. “It was only much later that I began to appreciate the other elements – the nonsense, the logical games and the clever theories which the nonsense hid. I studied mathematics, so I do believe that Carroll’s mathematical mind came up with things that seem nonsensical but are actually possible given a different mathematical frame.”

It is extraordinary that a story spun to entertain a six-year-old girl on a boating trip has continued to brighten the lives of generations spanning more than a century.

And so just like the way it began in the beginning, Alice in Wonderland remains what it is – a story to delight children.

“My greatest joy,” says Samit Basu, “was the completely context-free sizzle that went through my brain when I first read it as a child, and there’s nothing that can either truly explain or analyse that.”

**

Looking back through translations

On 4 October, 1866, Lewis Carroll wrote to his publisher Macmillan, stating, “Friends here [in Oxford] seem to think that the book is untranslatable.” But his friends were wrong as the editors of Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece, would tell Carroll if they could.

Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece documents the classic’s translations in 174 languages and over 9,000 editions and reprints. (Pictured in it is Alice Liddell, the little girl the book was written for)

This book, edited by Jon A Lindseth and Alan Tannenbaum, documents translations in 174 languages and over 9,000 editions and reprints of Alice in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass.

“There are nine translations of Alice into Tamil, plus an unpublished draft, a short story, a serialised story, and a graphic version,” says Dr Rajamanickam Azhagarasan, contributor to the book. “It was popular among those involved in the movement for children’s literature from the ’40s through the ’70s. Each translation was unique, depending on which aspect the translators wished to highlight.”

Alice has been translated in Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Konkani, Malayalam, Marathi, Oriya, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Nepali and Sinhala. Here (left to right) are translations in Malayalam (2000), Urdu (1981) and Oriya (2002).

Much like the way storytellers have always found new stories to weave out of the Indian epics, Alice’s translators in India have created different Wonderlands – for instance, by weaving mythological elements into the story.

“The Telugu translation of Alice was available as early as the mid-1950s,” says Suresh Kosaraju, trustee, Manchi Pustakam, Secunderabad.

Editor Sushama Sonak says, “Mugdhachi Rangit Goshta (The Many Coloured World of Mugdha) written in Marathi by short story writer GA Kulkarni was heavily influenced by Alice.”

In Malayalam, the first translation was published by Balan Publications. Lewis Carroll certainly influenced the well-known children’s nonsense writer in Bengali, Sukumar Ray, as well as Hemendra Kumar Roy, who wrote wonderful detective stories in Bangla and translated Alice in Wonderland: it is called Ajab Deshe Amala.

Even Vladimir Nabokov, the author of Lolita, translated Alice into Russian. According to translator Sergei Task, “By and large, [Nabokov] translated the text as is, except for Russifying the names (Alice/Anya, Mabel/Asya, and the Rabbit got a last name – Trusikov) and introducing pre-revolutionary forms of address such as barin (master) and vashe blagorodiye (your honour). Of course, with the playful verses, he had to take liberties – again, trying to adapt them for Russian readers.”

18 October 2015