POCKET PENGUINS

Introducing 20 Pocket Penguins

THE FUTURE OF PENGUIN CLASSICS

26 May 2016

A-format paperbacks

Pocket Penguins are the bold next step from the world’s most recognizable publishing brand. They are the future of Penguin Classics.

On 26 May 2016 we launch with a carefully curated list of twenty titles, highlighting a mix of the famous and unjustly overlooked that celebrate the pure pleasure of reading. Colour coded to reflect their original language, Pocket Penguins contain complete texts in a compact format designed to pick up, pocket, and go.

“These books are intimate, grand, funny, widescreen, painful, visionary – and we have been put on earth to make you want to read them!”

Simon Winder, Publishing Director

A REVOLUTION IN READING

In the space of one year, over 2.2 million Little Black Classics have been sold worldwide, demonstrating a huge new appetite for reading the Classics.

A RETURN TO COLOUR AFTER DECADES OF BLACK

Since 1946, Penguin has been publishing classics in winning formulas and pushing the boundaries of cover design. Our use of oil paintings on black covers paved the way for a look that dominates classics publishing today. Now the timeless tri-band simplicity and bold colours of Pocket Penguins will show the power of leaving authors’ names and titles to speak for themselves.

On the 70th anniversary of the first Penguin Classics, Penguin’s Art Director, Jim Stoddart, has produced a new design that is both approachable and contemporary.

“The new range blossoms from black into the technicolour of Penguin’s heyday. While this is a comforting nod to past Penguin, this is very much a series of books for the modern age.”

Jim Stoddart, Art Director

THE FIRST TWENTY

THE MASTER AND MARGARITA RUSSIAN

Mikhail Bulgakov

This ribald, carnivalesque satire – featuring the Devil, true love and a gun-toting cat – was written in the darkest days of the Soviet Union and became an underground sensation.

MRS DALLOWAY ENGLISH

Virginia Woolf

The lives of a woman preparing for a party and a young man suffering from shell-shock converge on one June day in 1920’s London, in Woolf’s great novel of time, memory, war and the city.

THE SECRET AGENT ENGLISH

Joseph Conrad

Set in an Edwardian London underworld of terrorist bombers, spies, grotesques and fanatics, Conrad’s dark, unsettling masterpiece asks if we ever really know others, or ourselves.

THE GOOD SOLDIER SVEJK CZECH

Jaroslav Hasek

Drunkard, malingerer, oaf and possible genius – the story of Czech soldier Svejk and his misadventures in the First World War is one of the most hilarious and subversive satires on war ever.

THE LOST ESTATE FRENCH

Alain-Fournier

A novel of desperate yearning and vanished adolescence, the story of Meaulnes and his restless search for a lost, enchanted world has the atmosphere of a dream and the purity of a fairytale.

THE CALL OF CTHULHU ENGLISH

P. Lovecraft

Mad, macabre tales of demonic spirits, hideous rites, ancient curses and alien entities lurking beneath the surface of rural New England, from the man who created the modern horror story.

THE BETROTHED ITALIAN

Alessandro Manzoni

Two lovers must face tyrants, war, riots, plague and famine in this teeming panorama of seventeenth-century Italian life.

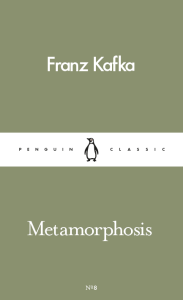

METAMORPHOSIS GERMAN

Franz Kafka

An ordinary man wakes up to find himself turned into a giant cockroach in Kafka’s masterpiece of unease and black humour.

THE NOTEBOOKS OF MALTE LAURIDS BRIGGE GERMAN

Rainer Maria Rilke

This dreamlike meditation on being young and alone in Paris is a feverish work of nerves, angst and sublime beauty from one of the twentieth century’s greatest poets.

THE HOUSE OF ULLOA SPANISH

Emilia Pardo Bazan

Set in a crumbling Spanish mansion, this gloriously comic and gothic novel follows the fortunes of an innocent young priest as he enters a world of moral decadence, sexual intrigue and corruption.

FATHERS AND SONS RUSSIAN

Ivan Turgenev

This humane, moving masterpiece of families, love, duels, heartache, failure and the clash between generations caused a scandal in nineteenth-century Russia with its portrayal of youthful nihilism.

OUT OF AFRICA ENGLISH

Karen Blixen

In one of the most passionate memoirs ever written, Karen Blixen recalls running a farm in Africa at the start of the twentieth century, and the love affair that changed her life.

WALDEN ENGLISH

Henry David Thoreau

One man’s account of his solitary and self-sufficient home in the New England woods, this is the original book about abandoning our ‘lives of quiet desperation’ and getting back to nature.

A PARISIAN AFFAIR FRENCH

Guy de Maupassant

Sparkling, darkly humorous tales of high society, playboys, courtesans, peasants, sex and savagery in nineteenth-century France, from the father of the short story.

THE BEAST WITHIN FRENCH

Emile Zola

Zola’s tense, gripping psychological thriller of adultery, corruption and murder on the French railways is a graphic and violent exploration of the darkest recesses of the criminal mind.

THE COSSACKS and HADJI MURAT RUSSIAN

Leo Tolstoy

Two masterly Russian tales of freedom, fighting and great warriors in the majestic mountains of the Caucasus, inspired by Tolstoy’s years as a soldier living amid the Cossack people.

THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO ENGLISH

Alfred Russel Wallace

The great Victorian scientist’s heroic adventures across South-East Asia, from Singapore to the wilds of New Guinea, encountering head-hunters, jungles, birds of paradise and new discoveries that would change the world.

THE RAINBOW ENGLISH

D.H. Lawrence

Following three generations of a family in rural Nottinghamshire as they struggle, fight, labour on the land and discover who they are, Lawrence’s rhapsodic, poetic and mystical work rewrote the English novel.

MY CHILDHOOD RUSSIAN

Maxim Gorky

In one of the most moving, raw accounts of childhood ever written, Maxim Gorky describes, with appalling clarity and startling freshness, growing up amid poverty and brutality in Tsarist Russia.

O PIONEERS! ENGLISH

Willa Cather

A rapturous work of savage beauty, Willa Cather’s 1913 tale of a pioneer woman who tames the wild, hostile lands of the Nebraskan prairie is also the story of what it means to be American.

For more information: Caroline Newbury, [email protected]

20 Feb 2016