Interview with editor and translator, Mini Krishnan

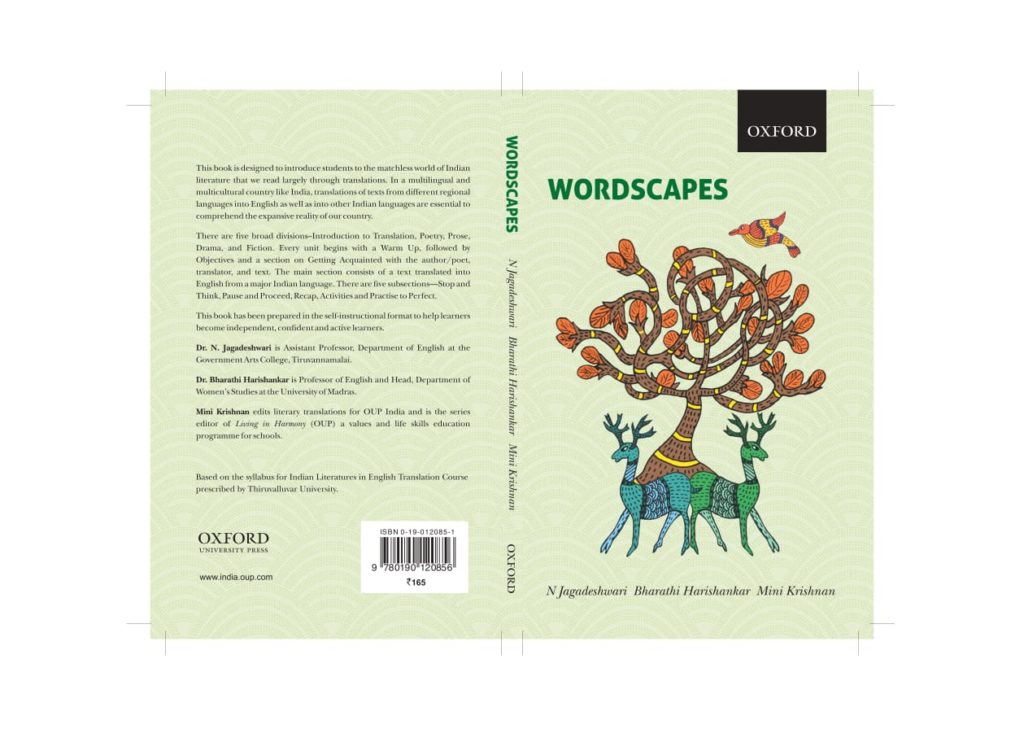

Mini Krishnan worked with Macmillan India (1980-2000) and with Oxford University Press (2001-2018) to source, edit and promote translations into English of works by Indian writers from 13 languages many of which won national prizes and are included in study courses both in India and in universities overseas.

She is currently co-ordinating multiple publishers to build a programme of Tamil-English translations. This is an initiative designed by the Tamil Nadu government and located in their Textbooks and Educational Services division.

1.How did you begin your career as an editor of texts translated from Indian languages into English?

Well…I think it is fair to say that it began as both an accident and an affinity for things Indian long submerged by training in English Literature! I always felt a vague dissatisfaction with the texts I was reading / studying but had no clear idea of how to access materials written by Indians. Nor how to relate them to what seemed to be important intellectual tools gained in UG and PG degrees in English Literature. In the late 1960s-early 70s when I was a student, books were not that easily available. Because my father was with the Deccan Herald (Bangalore) I got to read the books he received for review and that was about all. My college and university libraries did not stock books by Indian authors.

Seven years after my post-graduation I got an opportunity to freelance with Macmillan India in Madras. I was put to work on anthologies of prose, poetry, fiction and so on. Quite dull work really but I kept asking my editor why she couldn’t include some Indian writers other than Nehru, Sri Aurobindo and Tagore. “The members of Boards of Studies do not even consider other Indian writers worth teaching,” she said. I thought to myself that if I ever got a chance I would campaign for the inclusion of Indian writers in foundation English courses.

I got my chance when my editor (Viji Sreenivasan) left, creating a vacuum which I filled. I was a square peg in a square hole. A week later the Kerala Sahitya Akademi and Macmillan India signed agreements to produce a two volume publication titled Comparative Indian Literature edited by KM George; with 16 chief editors and 200 contributors, it was a stupendous work. The entire chronology of Indian literature was catalogued and described. Ancient Poetry (all the languages recognized at that time) Modern Poetry. Ancient Theatre, Modern Theatre. Fiction. Short and Long. And so on and so on. It was 4000 pages and took five years to push into shape. I worked on nothing else.

But where might all those Indian language works, described in this publication be accessed? Only a very small number of them were available in English translation. So, since fools rush in, I designed a project of modern novels from eleven Indian languages and tried to persuade Macmillans to invest in the idea. They were astounded. They were textbook publishers and I was their golden goose publishing for the school and college market. Why waste editorial time and money on translation? So I set about looking for support outside Macmillans. If I secured funding I would be allowed to do the project. For seven years I went from door to door trying to convince powerful institutions to part with some money for Indian literature. Mind you I had nothing to show anyone as a promise of what might be possible. Only a single failed translation by V Abdulla of Malayatoor Ramakrishnan’s Verukal.

Finally, in March 1992, my friends Valli Alagappan, her father, Mr AMM Arunachalam and her aunt Mrs Sivakami Narayanan who jointly ran the MR AR Educational Society of Madras agreed to fund me. I still do not know why they decided to help me. I had nothing to recommend me but my enthusiasm and determination. I received a letter saying that they would set aside Rs 80,000 per book for 50 books.

No one was more surprised than my highly commercial management but there was trouble. Though my Vice President R Narayanaswamy supported me, my Managing Director Sharad Wasani was unwilling to let me spend a lot of time on what he saw as an unsaleable project. When he received the forms seeking his approval he refused to sign. I wrote him, “You are the only person in the world who will refuse funding for his country s literature”and closed by offering to resign. Only two people from that time left — Jayan Menon and Sukanya Chandhoke— who will remember this.

Anyway, after Wasani changed his mind, I invited eleven eminent writers to be the chief editors for the languages I had selected for the project ( Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Gujarati, Marathi, Oriya, Bengali, Urdu, Hindi and Punjabi) and they helped to make up lists of five post-Independence novels from their respective langauges. Because I had been dealing with 16 chief editors on the C.I.L volumes I didn’t think this strange at all but anyone who discussed the project with me was astonished at the volume of work I had undertaken. It didn’t seem like work at all to me ! At last I was getting to do what I had really wanted to do when I entered publishing 12 years before.

Many important works were published in full for the first time in English: Brushte ( Outcaste) by Matampu Kunhukuttan, Randamoozham ( Second Turn) by MT Vasudevan Nair, Bharathipura by UR Ananthamurthy, Danapani (The Survivor) by Gopinath Mohanty, Subarnalatha by Ashapurna Debi, Ponniyin Selvan by Kalki and Karukku by Bama.

In all, between 1996 and 2000 when I left Macmillans I published 37 volumes. They went out of circulation a year or two after I left the company and the C.I.I.L Mysore bought the whole project including unsold stocks in 2007 with a view to republishng the entire list. It never happened because the Director (UN Singh) whose dream it had been, left the Institute.

2. What were the languages you first worked on? How many languages have you worked upon so far?

The first scripts I worked on were translations from Malayalam and Tamil. In all, I’ve worked on translations from Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Konkani, Marathi, Gujarati, Bengali, Odia, Hindi, Kashmiri, Punjabi, Urdu, and just one from Dogri.

3. How do you select which book is to be translated especially if it is a language you are unfamiliar with?

As I said because of the work I did on Comparative Indian Literature it wasn’t difficult to identify what needed to be translated particularly if the Sahitya Akademi had not already commissioned translations. Then again once the Macmillan project took off I was flooded with advice and suggestions. The difficulty was what to leave out. A great disadvantage is that I could not and therefore did not read the critical material on any of these works. I rely a great deal on the advice of others. But when it comes to translators I use a process of running trial drafts of different kinds of passages from the selected work — one might be a descriptive paragraph, a second something very emotional or lyrical, a third passage would cover conversation – to check the translator’s strengths and where s/he might back off, or skip or be lazy. The editing process can take anything from two drafts to six depending on the competence of the translator and the cooperation between all parties. Long silences, gaps in the process are not healthy for the project nor is impatience or being a speed queen the answer. As for the reception of a translation! Much depends on how well the publisher promotes the finished product. Publishing is only 50% of the responsibility. The other 50% depends on promotion and follow-up.

4. Do you think it is necessary for an editor to be familiar with the source language? If not, how can the editor ensure that the translation is true to the original text?

Of course it is important for the editor to know the source language but then in how many languages can one gain proficiency? The editor/ publisher must appoint reviewers who will read the translation carefully to ensure (as far as possible) that nothing has been left out or distorted. Then the editor can take over and polish in consultation with the translator and author.

5. What are the kind of guidelines you think an editor of translations should be bear in mind while working on a manuscript?

Listen very carefully to the voice of the author. Does it chime with the translator’s? It helps to have someone read out the original even if you do not know the language while you follow the English in a parallel reading. You cannot but help hear the inflexions and emotions as the reading proceeds.

Be respectful. Very important to gain the confidence of the translator. Make suggestions tactfully. Once the translator is convinced you are not out to destroy his work or appropriate it, he will breathe easy and work and redraft willingly. It helps to read other works from the same period and familiarize oneself with the language – bank of that time. You need to enter that world emotionally through images and atmosphere not just intellectually through words.

6. What is your definition of a “good translation”? What are the qualities it must have?

This is something I have been trying to figure out for 30 years! Sometimes a smooth read will fail to capture the imagination of the reader. Sometimes even if a translation is jerky and appears to be rushing along, it will work. I think it is a combination of inspiration and zeal on the part of the translator and very patient work on the part of the editor. The qualities? The language must bring the author alive. It must make you think “If XY had written in English instead of in Marathi this is how he might have phrased it”. Now it is all very well to say this to ourselves but to someone who is not Indian, this might still not work at all. Basically I think we should be translating first for our Indian market before trying to reach spaces and minds outside India.

7. When you began translating texts into English for the Indian market, at the time, most publishing houses ignored translations. Today the reality is very different. Most publishing houses have dedicated translation lists and even the local literary awards are recognising translators. What in your opinion are the pros and cons of this deluge of translations in the market — locally and globally?

It is extremely encouraging to see the increased interest in translations and the care with which they are produced but a worrying feature is the way publishers are responding to criteria laid out by the big literary bursaries and prizes for translation. There is a growing tendency to ignore works published more than 20 or 30 years ago and no one seems to want to do a fresh translation of a classic. Then there is the secret craving on the part of publishers to promote a translation as not a translation. So the translator’s name disappears from the cover page, a most unfair practice. I put this down to the second-classing of translations—as if they are something inferior and not worthy of being viewed as works of art in themselves.

8. Recently machine translations such as Google’s neural technology are making an impact in the space of translation. How do you feel about the impact of machine translation in the literary sphere?

Any technology which helps the human translator will be of enormous help I’m sure but I doubt whether it can supplant imagination and nuanced word choices. For mundane passages for instance this interview can be processed by Google translation but — a poem full of feeling and fire? I doubt it. An approximation would surely be possible but would it be good enough? I’ve always maintained that the translator is as much an artist as the writer of the original work.

9. Your name in Indian publishing is synonymous with translation evangelism. You have been responsible for kick-starting many notable projects. The current one being the Translation Initiative of the Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University (TEMU). Please elaborate more on this project.

Actually I did not initiate the TEMU project. That was designed by K Jayakumar the first VC of the University. It was a simple plan: an advisory committee selected works, I commissioned the translations and marketed the idea with multiple publishers. In some cases, the publishers already had scripts on hand; in other cases, I found the translators and did some light editing before handing over to the concerned group. The University signed agreements with the publishers to buy 300 copies at a discounted price and the publishers agreed to carry the logo and mission statement of the University in the selected works. I did not initiate any project other than the Macmillan list. In OUP I enlarged and diversified an already extant list which had not — till I began work in 2001— published a single woman writer. Nor had Dalit or Adivasi writers been considered. That was an arm I grew for OUP India and it has done well.

For a year now, I’ve been working with the Tamil Nadu Textbook Educational Services on a Tamil- English translation project modelled on the TEMU plan. Our collaborators in the first phase are OBS, Niyogi, OUP, Ratna Books, Harper Collins and Vitasta.

10. Can the art of translation and editing a translation be taught or is it a lived experience?

Commitment, determination and passion are crucial to sustained work in this area. To find a forgotten work, to convince people that it must appear in English, to struggle with the translator at its rebirth and to learn that a major publisher in the language of the original work decided to reprint the book (which had lain in a rabbit – hole for four decades) —- that is the best thing an editor of translations can hope to enjoy.

Strategies in translation can certainly be taught. Translator training is certainly possible and necessary but finally the translator is on her own except for her editor and together they complete the phantom work. It might succeed. It might not. It might succeed as an aesthetic product and bomb in the sales department. But then that is the fate of any human product which is judged by both ignorant people and by those who know far more than you do. No amount of reading about tennis or watching it on television can help you to be a good player on the court!

11. Translations are most often construed as being undertaken as a labour of love with little financial resources being available for underwriting the costs involved in the task. What are the economics of publishing translations in India? What has been your experience?

Love is great but it won’t put food on the table. Translations need financial support either from a patron or from another line of books from the same publisher who sets aside resources for the translations list.

12. What do you think is the future of literary translations in the world of publishing?

The world literary mart is only just waking up to the hidden power of translations and what they do to cross-pollinate creativity across cultures and civilizations. Consider all the talk about world peace! How can this happen if cultural understanding isn’t an organic process? One way to ensure this is to expose children and young adults to writing from different parts of the world at an impressionable time in their lives. Translation can help the humanities to make a brilliant comeback in a global sense. Comparative literature is impossible to teach without discussing the central role of translation. If we are to survive all the artificially orchestrated hatred and violence and misunderstandings created by politicians and power –mongers, venues of mutual understanding need to be very deliberately developed. Cultural competence, soft –skills — these are words one hears very often but what are we doing to build that theatre of human understanding? I think that if literary translations can be included in academic programmes and introduced into high-interest professions like management, finance and public policy it would help humanize these professions and give publishers the big print runs and inflow they need to keep doing what only they can do.

Note: Women Writing in India edited by Susie Tharu and K Lalitha (OUP) was a reprint of the Feminist Press publication, 1993, NY and not commissioned or developed by Oxford University Press.

5 November 2019