Tuesday Reads (Vol 5), 16 July 2019

Dear Reader,

Choosing a book or two to write about always throws me into a pother. The three mentioned in today’s post are not to be missed.

Writer and translator Shanta Gokhale’s autobiography One Foot on the Ground: A Life Told Through the Body is brilliant. Shanta Gokhale is known for her translations from Marathi into English but she is fluently bilingual in English and Marathi. One Foot on the Ground is an account of her childhood, her father’s insistence on sending her to England to complete her school and later University. She returned home to become a teacher and then later joined the PR team of Glaxo. Ultimately she became known for her work as a journalist/columnist, screenwriter, translator and writer. She quit her day job once her children were old enough. Most interestingly, as the subtitle indicates, this is an autobiography that documents the various stages of her life through memorable experiences pertaining to the body. From the first remembered instances of molestation by the cook, dental troubles, babies, cancer, glaucoma etc. Then there are those other quiet assertions of her identity and her self, like filing an affidavit in the court to use her maiden name while still married, allowing her ex-husband to share her apartment till he had found a place for himself ( which was not to be for some years!), revelling in the joy of having her own space, her own bed where she could stretch out and read/work, ultimately recognising that she “needed a room of her own to be the person I was”. The calm tenor and poise with which Shanta Gokhale discusses her life, her body, her responsibilities and her ambitions is delightful. One Foot on the Ground is like reading the testimony of a woman who lives her feminism and do so contentedly. ( Read an extract published in Scroll on 10 July 2019. )

The second book, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: A Novel is an extraordinary debut novel by award-winning queer Asian-American writer Ocean Vuong. Written in the first person by the narrator, Little Dog, it is a coming-of-age tale in America. It is about the boy, his Vietnam War veteran grandfather, his schizophrenic maternal grandmother and his mother who suffers from PTSD. It is a thinly veiled autobiographical account of Ocean Vuong’s life, of migrating to USA as a two-year-old refugee via a brief stay at a refugee camp in the Philippines. The precision of his writing, much as the fineness of description that is associated with poetry, is a remarkable transferance of creative talent into prose. The long beautifully crafted flowing sentences. In fact Ocean Vuong wondered in an interview if it was a comically futile effort. He had to contend with various multiplicities while also being very aware of the American lineage of biographies. Yet the agency as an artist is also very important to him. He adds that he was very inspired by the American idea that one can create a mythology for oneself.

Once at a writing conference, a white man asked me if destruction was necessary for art. His question was genuine. He leaned forward, his blue gaze twitching under his cap stitched gold with ‘Nam Vet 4 Life‘, the oxygen tank connected to his nose hissing beside him. I regarded him the way I do every white veteran from that war, thinking he could be my grandfather, and I said no. “No, sir, destruction is not necessary for art.” I said that, not because I was certain, but because I thought my saying it would help me believe it.

A coming-of-age novel that can be seen to exist firmly within the American tradition of literary biographies but at the same time is that of an Asian-American negotiating his adopted country. By writing this novel, Ocean has put together the best of literary traditions of his country of origin and his adopted country — the written word with the oral tradition and its folksy element. Thereby making it possible to speak of his schizophrenic grandmother and his mother who suffers from PTSD. There is plenty to unpack in this novel. It has many autobiographical elements which Ocean acknowledges in his various interviews but it has been announced as a novel. Ironically this is in the form of a long letter to his mother who is unable to read English. He states “the chance this letter finds you is slim — the very impossibility of your reading this is all that makes my telling it impossible.” At the same time Ocean Vuong rightly points out that “Conflict driven plot becomes its own protagonist” . Here is a wonderful profile of Ocean Vuong published in the Guardian. ( 9 June 2019).

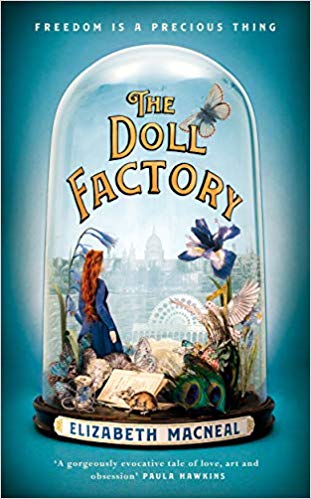

The final book is another debut novel that has been considered by its publishers “the most coveted debut of 2019, an intoxicating story of art, obsession and possession”. Elizabeth Macneal’s The Doll Factory is set in Victorian London, at the time of the Great Exhibition and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Doll Factory is about the heroine Iris who aspires to be an artist while employed with her twin sister painting dolls faces. Iris soon finds herself a part of the PRB. She is hired as a model. It is a fine mix of nineteenth century preoccupation with details and twenty-first century preoccupations of modern storytelling while being very aware of concepts like male gaze. There are moments of pure gorgeousness in the book especially when the author is describing the Great Exhibition.

Elizabeth Macneal is a graduate of the creative writing course at the University of East Anglia where she was the Malcolm Bradbury Scholar, and The Doll Factory has won her the Caledonia Novel Award. It has been sold to 28 territories so far, while TV rights have already been snapped up. Alan Massie puts it well in The Scotsman review:

It’s accomplished; there’s nothing raw about it. Today’s young novelists have all been schooled in the making of a novel and they have usually submitted drafts of it to fellow students as well as teachers, and taken their suggestions and criticisms on board. Their novels are far less clumsy, far less raw, than first novels so often were a couple of generations ago. The Doll Factory is a perfect example.

In the acknowledgements Macneal thanks a long list of people for their help and encouragement. No doubt they have all been useful. Nevertheless, it’s fair to assume that only she is responsible for the novel’s charm. It is indeed charming. But is it about anything that matters? Perhaps we shall have to wait for a second or even a third novel before knowing whether the author’s evident ability can carry her beyond charm so that she deals with matters of significance, writing something which has the reader engaged in both feeling and thought.

The Doll Factory will undoubtedly be seen on longlists and all the noteworthy literary prizes meant for debut authors. Ultimately Elizabeth Macneal may win one of the big literary prizes for a later novel she writes, by which time she will have rid herself of all the creative writing school learnings and learned to be confident of her own voice. She will have learned to trust herself.

For now enjoy this wonderful Twitter thread by Elizabeth Macneal describing how the exquisite book cover was designed:

One Foot on the Ground, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and The Doll Factory are three unmissable books of 2019. They have the incredible quality to stay with the reader long after the books are over and done with.

Enjoy!

JAYA

16 July 2019