“Dark energy. It’s the energy that helps the universe keep expanding. You might call it a part of the universal life force.”

That sounded vaguely familiar.

“My Baba always tells me we’re all connected to energy — trees, wind, animals, people, everything.” I tried to get my ragged breathing under control. “He says that the life energy is a kind of river flowing through the universe.”

And that our souls are just a bit of that river water held inside the clay pitcher of our bodies?” Neel smiled at my surprise. “Year, I know that story too. They say that when our bodies give out, that’s just the pitcher breaking, pouring what’s inside back into the original stream of universal souls.”

“So no one’s soul is ever really gone,” I finished, repeating the words that Baba had said to me often.

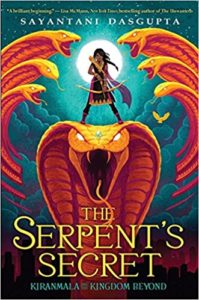

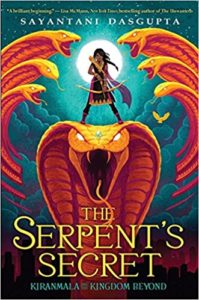

Sayantani Dasgupta‘s The Serpent’s Curse is a delightful fantasy story about a twelve-year-old girl, Kiranmala, who sulks at the idea of being dressed up as a princess for Halloween. She refuses to believe her parents when they claim Kiranmala is a genuine princess and on her birthday ( which alas falls on Halloween) she must dress up appropriately. It is on her twelfth birthday that all sorts of odd things begin to happen. She discovers her parents have disappeared leaving a moving map in their wake for her assistance, two princes have arrived on winged horses to escort her, there are monsters in her backyard and much, much more. It is an exciting adventure she sets off on to locate her parents while trying not to get entangled in the affairs of the Serpent King and the Rakkhoshi Queen.

The Serpent’s Curse is a mish-mash of desi folklore and myths combined with the American experiences of an immigrant family told at a brisk pace. Even though the fantasy elements are familiar and many of the stories told are retellings of well-known Indian folklore, it really does not matter. The beauty of age-old stories is that they can be told once more by a master storyteller and still be magical. The same holds true for The Serpent’s Curse. The fight between good vs evil, the Serpent King / Naga, the Rakkhoshi Queen / Evil Queen, the Underworld, princes and princesses etc.

Book review

While this is being promoted as YAlit an eight-year-old reader I met was absolutely charmed by this book. The little girl told me solemnly “I picked up this book at the school book fair because the cover was so lovely. I am now enjoying the story too.” Then at my request she proceeded to write a short book review as well though in her note on the left hand side says it is an “interview”. This is what she wrote:

Interview of The Serpent’s Tail

I enjoyed the book a lot because there were spells, snakes, mysterious parentage and magical lands.

The story is about a girl who had annoying parents and one day she realized that her parents were gone and she set off with two princes one half demon other human and she realizes that her mum is actually someone else and so was her dad. Her mum is actually a moon maiden and her dad is the king of serpents!

I picked the book because it had a cool cover and serpents are cool.

I rate this book: 0/4 serpents and 4/4 moons

The action in The Serpent’s Curse moves swiftly. The dialogue is never dull despite incorporating a lot of “Indianisms”. Having grown up on a feast of stories and desirous of sharing this rich storytelling tradition prompted Dr Sayantani Dasgupta to create her own books that retell Indian myths and folklore for the youngsters of the Indian diaspora. Having said that the book works equally well for everyone! The author is a pediatrician by training but now teaches narrative medicine/health humanities at Columbia University. It probably explains the chatty and accessible style of her storytelling. There is a lovely rhythm to the pace without a word out of place. She acknowledges her colleagues for inculcating in her that “stories are the best medicine”.

The Serpent’s Tale is well worth checking out!

Sayantani Dasgupta The Serpent’s Tale Scholastic, New York, USA, 2018. Hb. Pp. 350 Rs 495

31 May 2018