Interview with Slovenian writer Anja Mugerli

Author photograph by Saša Kovačič

(C) EU

This interview is facilitated by EUPL and funded by the European Union.

I am posting snippets of my correspondence with Anja Mugerli as it would give readers an insight into how she intermingles folkloric elements in to contemporary fiction.

Dear Anja,

Thank you for sharing the two PDFs of your stories in English translation. I have been pondering over the stories for a while now. Your stories operate at so many levels. They require the stories to be read over and over again and there is always something new to discover. I am not sure if you intended it, but at one level it is a straightforward short story. At another level, particularly if read again, it has a “folklory” air to it. I am not sure how to spell it out any clearer. Then, your fascination with the body without being voyeuristic or sleazy but in a calm, matter-of-fact tone, is lovely. It is almost as if a confident female gaze is over the body. and owns it. It is a very empowering feeling while reading your fiction. Thank you.

Dear Jaya,

Thank you for your very interesting questions. I’ll be happy to answer.

Anja

****

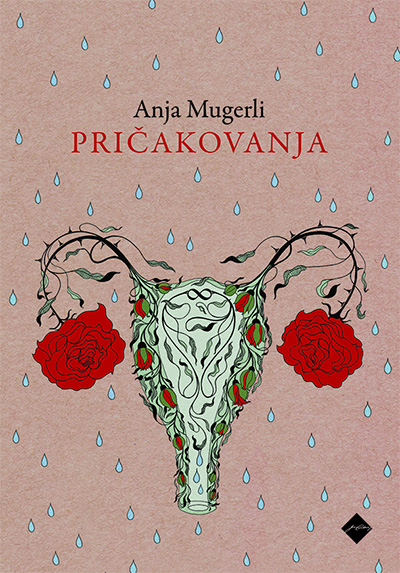

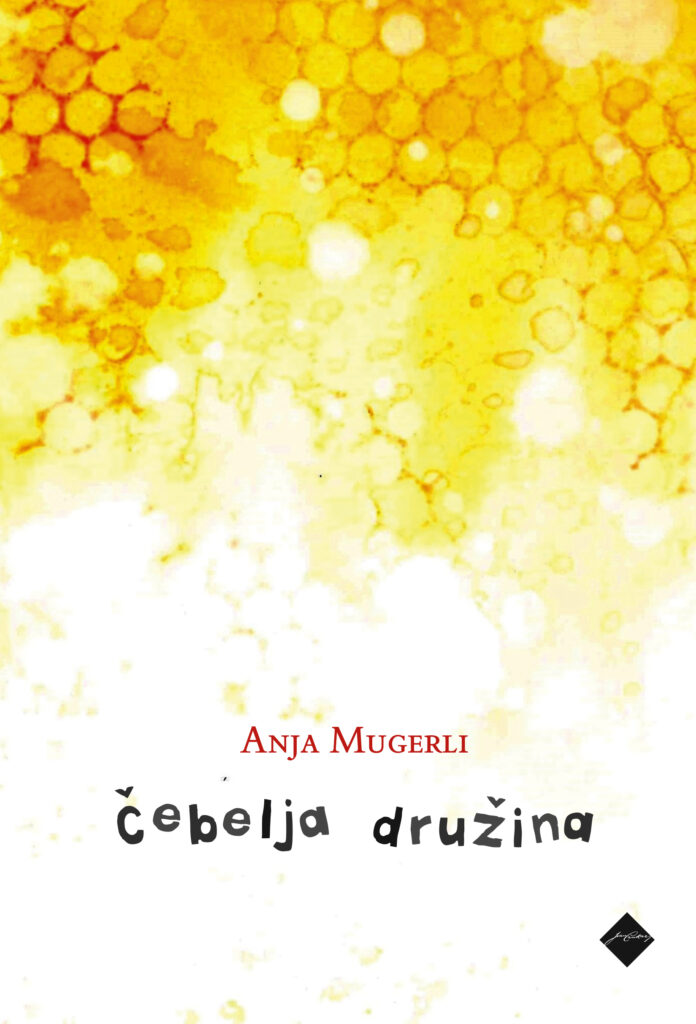

Anja Mugerli, born in 1984, is a Slovene writer. Her debut, the short prose collection Zeleni fotelj (Green Armchair), was published in 2015 and in 2017, her first novel, entitled Spovin, was nominated for the Novel of the Year Award in Slovenia. In 2021, her short prose collection Čebelja družina (Bee Family) won European Union prize for literature. She graduated with a degree in slovenian studies and has a master’s in performance studies and creative writing. She lives and works in Nova Gorica, on the border of Slovenia and Italy. In 2023, was published her second novel, entitled Pričakovanja (Expectations), by Cankarjeva založba.

Q1 How and why did you start writing fiction?

I grew up surrounded by books. I was a very shy and quiet child and sometimes it was hard for me to make friends. I guess what was missing in my real life I found it in books and when I grew up, I realized that I can express myself in writing. After I finished my studies, I decided I want to start writing seriously and I started sending my short stories to Slovenian literary magazines. More I wrote better my writing became and in 2014 I send my best stories to some editors because I wanted to publish a book. A year later my first book, a collection of short stories Zeleni fotelj (Green Armchair), was published. The book was very well received in Slovenia and since then I wrote three more books, two novels and another collection of short stories Bee Family, that received the European Union Prize for Literature. It was translated in Croatian, Macedonian, Hungarian, Italian and Bulgarian. Other translations will follow.

Q2. You are a polyglot. English, Spanish, Italian, and Slovene are the languages spoken by you. How does this familiarity with languages and thus, with different cultures impact your writing?

Slovene is of course my mother tongue. From other languages the closest to me is Italian because I live in a city on the border with Italy and I was in contact with this language form early childhood. English and Spanish I learned in school. Understanding different languages means that I can also read books in English, Italian and Spanish. Reading a book in original language is a different experience than reading it in translation. I often read the same book first in original language and then in Slovenian translation. An advantage of understanding different languages is also that I can read a book before it’s even translated in Slovenian. All this affects my writing. When I write a book about specific theme, I read other books that deal with this topic. In this way I compare different views and I try to look at the theme from other angles. This definitely broadens my horizon. Sometimes I use different books as references. In my novel Pričakovanja (Expectations) for example, I related to the female authors like Rachel Cusk and Sheila Heti who in their novels write about motherhood and womanhood.

Q3. What is it about cultural mappings that interests you?

In my book Bee Family, I explored different old customs and rituals specific from old Slovenian culture. Because I wanted a specific, darker atmosphere in the book, I chose the customs and rituals that deal with a little more obscure topics, for example burials. I knew about some customs, about others I found out during my research. There are a lot of old customs that are not used any more but they are still part of our culture’s heritage. I think it’s important to remember them and their role in past culture, and since many people don’t read ethnological articles, I think it’s a good thing to write about it in fiction. I like literature from which I learn something new, in which it’s not only about the story.

Q4. Would you self-translate your books, say from Slovene into English or even Italian? If yes, then what are the safeguards you would put in place, so as not to tinker with the text too much? Or would you merely translate the Slovene text as it has been written into another language?

In the past I actually translated a few of my texts from Slovenian to Italian. They were dramatic texts for a competition held in Duino in Italy. Two times I received the second prize, so I guess the translations were not bad. Today I wouldn’t do it anymore. I love writing in Slovenian. I can think, explain, interpret best in my own language.

Q5. You seem to be fascinated by the body. Why?

I think in western culture everyone is fascinated by the body – with this I mean of course female body. Since we are little girls, we hear and see everywhere how should a female body look like and also how it shouldn’t. This applies to films, tv-series, commercials and nowadays social networks, but it doesn’t stop there. Girls and women are confronted with comments on their bodies also in their social circles, from their classmates, coworkers and family members. The people who think they are allowed to comment on your body are often men (but not always!) and therefore also this myth of “perfect” body was made by men. I’m interested in women’s experience of their own bodies. How does it feel to be constantly aware of your own body? Because I think that women are constantly aware of their own body: how does it look, does it fit the society “standards”, what you think is wrong with it? Can your body get pregnant and can you have children? This is another thing that is very important in our society. Are you still a woman if you can’t have children? Or if you don’t want to have children? In my writing I try to turn the focus from “how should” to “how does it feel”.

In my novel Pričakovanja (Expectations) I write about a couple who can’t have children. The protagonist Jana is confronted with her own expectations and longings and with expectations of society. She is married, she finally has a steady job, she and her husband just bought a new apartment, the next step is a child. It seems that everyone around Jana expects that she will get pregnant. If she can’t get pregnant naturally, the medicine will help, it’s as easy as that. But during procedures of artificial insemination Jana feels more and more alienated from her body. She is reduced to her uterus, ovaries and cells and she gradually starts to lose contact with herself. The fact that the procedures of artificial insemination don’t succeed doesn’t help. Jana begins to think about motherhood. What does it mean to be a mother, is this really the only way she can live a full life, is it such a tragedy if she will never have children, what are the advantages of not having a child? She also realizes that it’s sometimes very difficult to separate your own expectations from expectations of others.

Q6. What is it about folk tales that intrigues and you wish to experiment with in your literary fiction? What are the technicalities that charm you, apart from folklore being a fine example of storytelling that has withstood the test of time. Can these be used and adapted with sophistication in modern stories?

In my book Bee Family, I explored old customs and rituals that are specific to Slovenian culture but can also be related to Slavic folklore. I never wanted to write about the past, instead I wanted to place these customs and rituals in today’s time (only one story happens in the past, during Second World War). I personally see old customs as a link to our ancestors and their way of life. I like the magic and secrecy of it, but I’m aware that nowadays society is very different, the values changed. Because of this, in my stories I tried to rethink old customs and rituals in a way that their main role changed. For example, in the first story of the book, the dance with the chair takes another role in the protagonist’s life in comparison to the old woman’s. If the dance with the chair in old woman’s life was important because during it, she found her future husband, the protagonist uses this old custom differently. In this way she breaks the tradition but on the other hand it’s because of this custom that she takes her life in her own hands. These customs and rituals often help my protagonists but not always in the way the reader may expect. My translator into Croatian said to me that these unexpected turns were exactly what fascinated her about the book. I see tradition as an important part of our culture, but I also think that we should rethink some old customs, see if they still make sense in the life we live today. Some cultures for example still blindly follow some customs that are hurting people and animals and nature.

Q7. How would you define femininity? Why is it that I get a sense from the few stories of yours that I have read, it is a concept that you wish to tussle with?

I think about this question a lot and I also try to integrate it into my writing, so I guess your sense is correct. What does it mean to be a woman? I often think about my mother who passed away four years ago. She was the first female role model to me. She was a very kind woman who always put her family first. She would do anything for us, her children. Some would say that this is a very natural thing, maternal instinct, but I personally know many women who don’t feel this way about their children or who even won’t have a child because of it. Are they less women because of it? I don’t think so. In her caring for others my mother completely forgot about herself. I see femininity as an ambiguity, always keeping balance between your own needs and wishes and expectations of family, friends, society. Some women, especially older generations, couldn’t handle this balance and they lived like my mother, they never put themselves first. It still happens today. I know many young mothers who deal with sense of guilt whenever they choose to put themselves before their child. I don’t have children, but I think you can’t expect to raise a child, who is sure of himself and who loves himself, if you as a mother don’t feel this way about yourself. It’s always about projection.

Q8. Your authorial comments in the stories are astute and you etch characters brilliantly. They are memorable. How do you observe people in real life?

As I mentioned before, I was that child that didn’t join the play or quarrels with other children. Instead, I’ve rather observed the behaviour of others, not only my peer but also adults. I’m an introvert and as you may know introverted people prefer solitude and conversations one-on-one than big gatherings. But because our society (with “our” I mean Western) is more extrovert oriented, introverts are sometimes forced to act in extroverted way, for example if they want to get a job. Some years ago, I read a beautiful book about introverts, Quiet by Susan Cain, and the author during her research found out that introverts often imitate the behaviours of extroverted people. They do this so they can survive in hyperactive western society. I found myself in this description and more I think about it more I’m sure I did/do the same think. I observe people, but I don’t stop with their behaviour, I also focus on their moods, fillings, reactions etc. I use all of this in my writing and in creating of my protagonists.

Q9. Women writing about families tend to get mired in a lot of domestic detailing, which in its own way needs to be articulated and made visible. Yet, in your fiction, you take it one step further and probe the grey spaces between relationships and explore the “what if”, without underlining it. Are these conscious acts in your craftsmanship?

In connection to my previous answer, I would say that in my writing there isn’t a lot of action. Although I observe different people and use the material in my writing, I simply can’t write from the focalization of an extroverted protagonist, because I don’t know how it feels to be extroverted. Instead, I focus on the things that interest me the most: the inner life of my protagonist, their psychology, their relationships and how they are being shaped in these relationships.

Q10. Do you have any Slovenian author/book/literary website recommendations for readers?

I would recommend writers Lojze Kovačič and Ana Schnabl (their books are also in English), and Slovenian poetry which in my opinion is very good. My favourite Slovenian poets are Miljana Cunta, Veronika Dintinjana, Maja Vidmar, Barbara Korun. I would also recommend they visit websites Airbeletrina and Vrabec Anarhist. Together with my two colleagues I edit literary newspaper November and your readers are very warmly invited to check our Facebook page and Instagram.

Disclaimer: This paper was written under the European Union Policy & Outreach Partnerships Initiative with the view to promote European Union Prize for Literature awardees. The publication was funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.