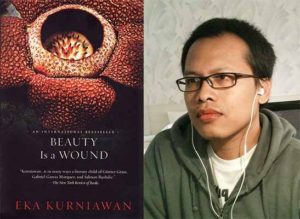

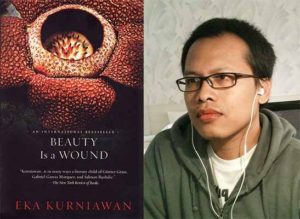

( My interview with award winning Indonesian author Eka Kurniawan was published on literary website Bookwitty on 6 February 2017. In India the books have been published by Speaking Tiger Books.)

( My interview with award winning Indonesian author Eka Kurniawan was published on literary website Bookwitty on 6 February 2017. In India the books have been published by Speaking Tiger Books.)

Award-winning Indonesian author Eka Kurniawan, whose writing, often compared to Gabriel Garcia Marquez, is an exceptional blend of myth-making, supernatural, fantastical, historical facts and horrendous amounts of violence. Told with such a flourish, his storytelling is unforgettable. Kurniawan was born in Tasikmalaya, Indonesia, in 1975 and has a degree in Philosophy. He writes novels, short stories, as well as non-fiction pieces. Beauty is a Wound and Man Tiger are two novels set in unnamed places with all the characteristics of Indonesia. His third novel to be published in English,Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash, will be available in July 2017. Eka Kurniawan kindly agreed to an interview for Bookwitty:

How and why did you get into writing fiction? What is your writing routine?

First of all, it was just for fun. I read some stories when I was a teenager, and I tried to write my own versions. I shared my stories with some of my friends. When I studied philosophy in University, sometimes I got bored with my study and skipped my class to go to library and read a lot of classic novels. And then I found a book by Knut Hamsun, Hunger. After I read it, I felt like I wanted to be a writer. So I started to write stories, seriously. My writing routine? I don’t write everyday. I always think that I am more a reader rather then a writer. I read anything every day, and only write something when I want to.

Who are the writers who have influenced you?

Like I already mentioned, Knut Hamsun. I love his deadpan humor and how he discovered his characters. And then there are three great Indonesian novelists: Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Abdullah Harahap and Asmaraman S. Kho Ping Hoo. The last two are a kind of genre writers. They wrote horror and martial art novels. I can make a very long list of writers that I believe have influenced me, but let me add these three writers: Miguel de Cervantes, Herman Melville, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Your storytelling is told with such a flourish that at times it is very visual or creates a strong physical reaction much like a response to watching a theatrical performance. While writing, how conscious are you of the reader’s response?

I am very conscious about the reader, but that reader is me. When I write something, at the same time, I always place myself there as a reader too.

“Magic realism” and “historical fiction” are how your books are described but how exactly would you like your special brand of storytelling to be known as?

I never think about it. People can give me any kind of label they please. But let’s be honest: in my novels, there are not only historical or magical elements, but you can find romance, saga, fighting, horror, adventure, even political and social criticism. I prefer to see myself as an adventurer, with all the literary traditions as my map.

I prefer to see myself as an adventurer, with all the literary traditions as my map.

Your stories seem to rely heavily on the oral storytelling narrative form as the structural basis allowing you the flexibility to expand and repeat details and incorporate supernatural elements…

It is something inevitable. I grew up listening to a village storyteller when I was still a kid. And then there was also drama on the radio, told by one particular storyteller. I was very fascinated by all of these stories, especially because I had only read a small number of books at that time. The stories were usually about village legends, full of monsters, jinn, beautiful ladies and brave men. Many of these stories I actually retold in my novels, including the princess who married a dog.

There are so many brutal aspects of sexual violence which you explore in your stories. Why?

First, when you take a look into Indonesian history (maybe even world history), you can’t help but find yourself faced with this kind of violence. It can be sexual, physical, mental or political violence. Second, I wrote my first novel just two years after the fall of Suharto’s dictatorship. It was time for us to be bolder in writing, to open all these scars in our history and face them. Third, I used to write stories in a “matter of fact” manner, I don’t want to hide things.

You write with the sensitivity and understanding of a woman, often sharing her point of view, making the stories seem more feminist than what some women themselves pen and yet the plots move with a predominantly male gaze. Is this a conscious decision on your part?

It was a conscious decision. Actually, my first two novels were inspired by some women, and they are really at the center of my novels. I tried to place myself from their point of view. It is always something important for me as a writer to be there, to know how they feel, how they see the world around them, and how they react to something.

The strong women characters in Man Tiger and Beauty is a Wound make choices which they follow through only to be labelled by society as insane. Why and how did you choose to create these women?

I think they just appeared like that in front of me. These two characters are very different from each other. They are strong, die-hard, but have different reactions. I never write stories with a plan. I usually just have a small idea, and develop it gradually. The characters come out one by one. I rewrite it several times, and the characters, including these two women, become more complex and have their own personality in the end.

Dewi Ayu (in Beauty is a Wound) remarks “The best stories are in religious texts”. Your stories seem to imbibe a lot of storytelling elements from the Hindu epics, the Bible and the Quran. How have these stories influenced you? What are the challenges posed in transference of popular tales when trying to recreate or apply them in secular literature?

My grandmother used to tell me stories from the Quran, and my father taught me to read it. So I am very familiar with these stories, as well as stories from the Bible (I read it later) as they are close. I discovered Hindu epics from wayang (puppet) performances, that usually used Mahabharata or Ramayana epics. The challenges occur with the fact that these stories are very popular. Many writers and storytellers retold them. I just picked the basic ideas and retold them in my own stories that have nothing to do with religious aspects, but with a parallel allusion to them.

Are the English translations true to the original Bhasa texts? How closely did you work with the translators – Annie Tucker and Labodalih Sembiring? Also why did you choose separate translators for the books – it is a slightly unusual practice given how authors and translators tend to forge a long term relationship.

It’s almost true. I worked very closely with the translators and we tried our best to render the original into English. Of course we faced some problems with grammatical and word nuances, as Indonesian and English are very different, and we discussed this a lot. Those two books were acquired by two different publishers. Verso and I approached Labodalih to translate Man Tiger after we tried some translators, and around the same time Annie Tucker proposed to translate Beauty Is a Wound, later acquired by New Directions. So, that’s why I have two translators.

Given the time lag between your novels being first published and then made available in English do you think having Indonesia as the guest of honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2015 helped in discovering contemporary Indonesian writers and making them available to the English-speaking world?

To be honest, before the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2015, I knew nothing about that. My books were published in English translation the same year, but we prepared them three years before, in 2012. But of course, as guest of honor at the 2015 Frankfurt Book Fair, this gave us an opportunity to be discovered, including my books. Publishers started to wonder about Indonesian literature…

Who are the Indonesian writers – based in the country or of the diaspora – that you would recommend for international readers?

Pramoedya Ananta Toer, of course, and Seno Gumira Adjidarma.

7 February 2017

The

The