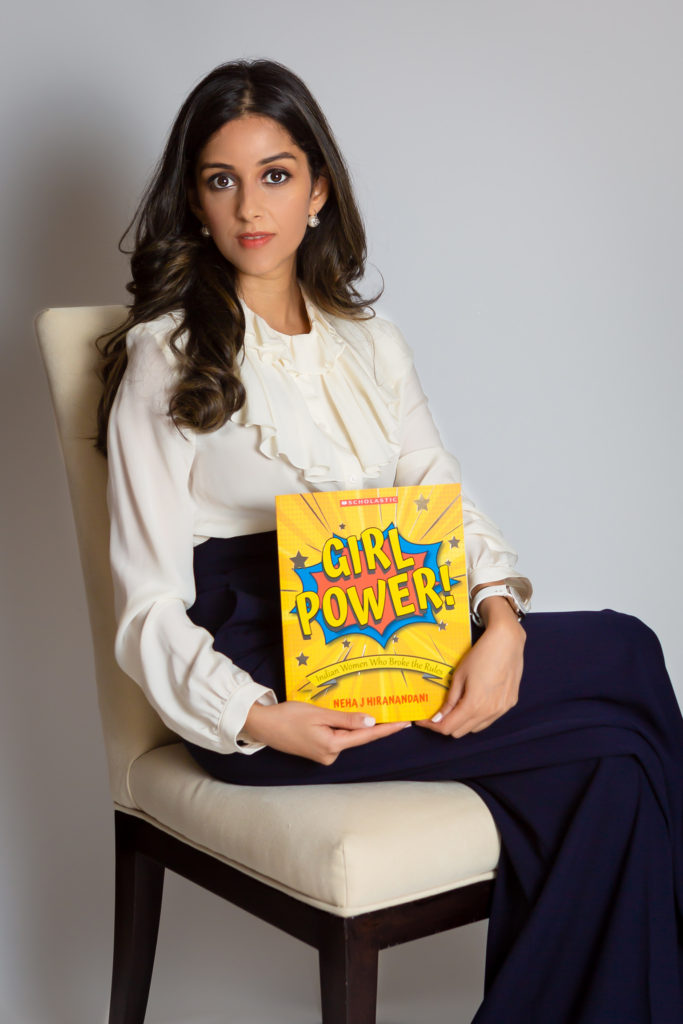

Interview with Neha J. Hiranandani on “Girl Power!”

Ever since the phenomenal success of Rebel Girls some years ago there has been a proliferation of books tom-tomming about the achievement of girls/ women, many of whom whose contribution to their respective sectors has been silenced for an extremely long time —an unforgivable act. Yet with the popularisation of movements like #MeToo and the visibility of such girl-centric literature in popular culture has made a remarkable case for many more such books to appear. The danger lies falling into the trap of emulating a successful formula and creating a damp squib or creating a triumphant collection such former journalist Neha J. Hiranandani’s feisty Girl Power!

It is a challenging task to visually and succinctly represent a core idea, more so an idea that seemingly goes against the “norm”. And this is why Girl Power! is so magnificent. It stands out from much else that in this space for it puts together beautifully a profile that has charmed the author. It is as if the woman whom Neha Hiranandani is writing about has really moved her in some way. Otherwise the absence of living legends such as activists Aruna Roy & Medha Patkar, writer Arundhati Roy, historian Romila Thapar, wrestler Vinesh Phogat etc remains inexplicable. For there seems to be no other explanation, save Neha’s subjectivity, for this very disparate collection of women profiled in Girl Power!

Neha Hiranandani’s fascination for her project manifests itself in the funky descriptor she offers after every name. It is super cool, so in keeping with the loud, assertive and sparkly book cover as if to say, “We women are proud of our achievement and are here to stay!” It effectively communicates her passion with younger readers.

****

Neha J Hiranandani is a writer whose columns have appeared in The Indian Express, Huffington Post, NDTV, and Vogue among others. She holds degrees in Literature and Education from Wellesley College and Harvard University.

Here are lightly edited excerpts of an interview conducted via email:

1.How did the idea of doing Girl Power! come to you?

My 7-year-old daughter, Zoya absolutely loved Rebel Girls. As a mother, I was so happy to see her being inspired by incredible women from around the world. But then one day she came to me clutching her beloved copy of Rebel Girls and asked sadly “Does India only have two rebels?” pointing to Mary Kom and Rani Laxmibai. Of course I immediately wanted to tell her all about the phenomenal women that India has had – our rule breakers, our mavericks, our smashers of ceilings. We spent the next few months discovering these women together. It was magnificent! I quickly realized that these were stories that all our girls – and even our boys – should hear.

2. There is a deluge of women-centric profiles in the market. Why is Girl Power! special?

I was very lucky to work with an incredible artist – Niloufer Wadia – whose illustrations have brought these stories to life. Unlike other books which follow a standard ‘one-page text + one-page illustration’ format, Niloufer and I wanted the text and the illustrations to work together. And so, every page of Girl Power! has the story and the artwork talking to one another which makes for an incredible reading experience. That, and I think the selection of women is very special!

3. How did you identify the women profiled in the book? Whom did you have to drop from your original list and why?

This was easily my favourite part of the project! I was clear that this wasn’t going to be just a list of accomplished Indian women – the women in this book had to be mavericks, ceiling smashers! And so I set about finding the stories and really, what stories they are! Every story made me feel me proud to be Indian all over again. You will meet a spy princess who parachuted into France, a warrior queen who defended India from the Portugese six times! There’s Subhasini Mistry who worked as a maid before winning a Padma Bhushan for healthcare, and Chandro Tomar, the octogenarian sharpshooter, popularly known as Revolver Dadi. Of course, there are some household names as well including PV Sindhu and Priyanka Chopra. But personally, I am very proud of the untold stories. They were so exciting to discover!

I have tried to be as inclusive as possible. Girl Power! includes stories from across the country, across industries and across time periods. I also tried to pick stories that had an identifiable ‘Kodak moment’ that could be written coherently in 300 words or less. This is easier said than done, especially given that all of these women have led very layered and nuanced lives!

With that said, I am the first to admit that this is not an exhaustive list – that would run into volumes and is well beyond the scope of this project.

4. The descriptor used as a subtitle in every chapter encapsulates the spirit of the woman profiled vividly. For example, “Raga Rockstar” for M S Subbulakshmi, “Accidental Entrepreneur” for Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, “Rule Breaker” for Dakshayani Velayudhan, “Inspirational Archer” for Deepika Kumari, or “Daredevil Doctor” for Anandibai Joshee. How did you come up with these fascinating descriptions?

These women have led such interesting lives, it would be a failing on my part to not give them interesting descriptors!

5. Girl Power! comes across as a broad sweep of profiling women across socio-economic classes giving the impression as if popular stories were incorporated. What kind of research methodology did you employ particularly what were the oral histories that you accessed?

This book will always be special to me for so many reasons. And perhaps, the most important one is that it connected me to many incredible people – men and women – who I’m grateful to have met. Apart from the internet research and the scouting in libraries, I knew that many of the stories were going to come from conversations. And so they did! Over cups of tea in the most unlikely of places – from railway stations to parks – I have spoken to people about the women who have moved them, inspired them. Some of the stories didn’t work out because I couldn’t confirm their factual accuracy but others did. For many parts of the book, I wanted to move beyond the well-known women and tell stories of ordinary women who have done extraordinary things. It was in that quest – of finding the ordinary-extraordinary woman – that our unmatched recounting of oral histories became important. Sometimes, it’s just about having the conversation!

6. Every chapter consists of a sprinkling of quotes by the women profiled. Such as ‘As long as I moved around with Mankeshaw [her husband], people did not take me seriously,” said Homai Vyarawalla, the photographer or “No field of work belongs to any gender”, says Harshini, the firefighter or actress Priyanka Chopra attributes her success to following the three Fs – “by being fierce, by being fearless and by being flawed”. Where are these quotes from as there are no bibliographical details provided?

Along with the team at Scholastic India, I was meticulous in making sure that every fact was double-checked. Many times this meant watching several documentaries for a 5 word-quote or finding obscure books and articles in dusty libraries. While there is no bibliography in the book, we have maintained an exhaustive back-of-house bibliography! So for instance, the quote by Homai Vyarwalla is from an article in the Hindu, the one from Harshini Kanhekar is from an interview with Jovita Aranha, and the one by Priyanka Chopra is from a lecture she gave on ‘Breaking the Glass Ceiling: Chasing a Dream’ at a Penguin event back in 2017.

7. Some profiles make passing references such as to Amrita Shergill’s “South Indian trilogy” or Dipa Karmakar’s “new book” or to a “rifle club” in Chandro Tomar’s neighbourhood which her granddaughter was attending – all very intriguing and remains unexplained? Was it a deliberate intent on your part to leave these as is to encourage inquisitive readers to delve into some research of their own?

Absolutely! This book gives a quick insight into the lives of these incredible women. It provides the ‘hook’ of an interesting time in that woman’s life to lure the reader in. The ultimate idea is that a child finds that ‘Kodak moment’ interesting and says “Hey, that’s cool I didn’t know that but now I want to find out more.”

8. How important is the picture book format to communicate with young readers particularly when it is a critical idea such as challenging rules, mostly patriarchal, to pursue your dreams?

I think it’s critical! Visuals go a long way in keeping a young reader interested and this is especially so in a format like Girl Power!’s where the text and illustration talk to each other on every page.

9. With this book are you addressing both boys and girls? What impact do you hope to create?

One might assume that this book is only addressed to young girls. That would be a terrible mistake. In fact, if anything, I think this book is critical for our young boys. For far too long, our boys have seen us in certain roles – as a mother, as a wife etc. It’s time for them to see Indian women succeeding in places that were traditionally demarcated as ‘men only zones’ – as wrestlers, as scientists, as entrepreneurs! If nothing else, it will help them understand what’s coming down the pike in the future!

10. Were these stories tested on younger readers before publication? If so what was their reaction? Did you incorporate any of their suggestions in the manuscript?

My daughter and her friends were invaluable as I wrote Girl Power! Those kids were my first editors! During play dates, I would read out entire stories and meticulously comb through their suggestions. Many profiles – such as Rani Abbakka – were rewritten on the basis of these editorial inputs! Several times, the kids wanted more details on an event or character that they found interesting. So for instance, in the Rani Abbakka profile, they wanted to know exactly how she defeated the Portuguese armada. That’s when I knew I had to include the part about how Abbakka secretly gathered her best soldiers in the middle of the night. The kids were fascinated when I told them that Abbakka instructed her soldiers to attack with hundreds of coconut torches and agnivaan– flaming arrows dipped in oil – all at the same time. The arrows lit up the night sky setting the Portuguese ships ablaze. These inputs brought so much colour and detail to the profiles and I’m so grateful to the kids! I think it was those inputs that have sharpened the profiles and created the final product.

11. Did you work closely with the illustrator? Did you help the illustrator select an image upon which to build the illustration?

Niloufer Wadia is a wonderful, prolific illustrator who can handle many different artistic styles with ease. I did make suggestions for some profiles; for example, Bula Chowdhury is an ace swimmer who once said “I should have been born a fish.” And so for Bula, I asked Niloufer if we could create something dream-like with Bula in the waves, half-woman and half-fish, almost a mermaid. That is easily one of my favourite illustrations in the book. For other profiles, Niloufer created something breathtaking on her own; Priyanka Chopra’s illustration is half from an iconic Hindi movie in traditional Indian attire and half FBI agent, a character from her show Quantico. That was all Niloufer!

12. Would you describe yourself as a feminist or as someone who feels strongly about women’s issues?

To my mind, there is no other way to be!

To buy on Amazon India: https://amzn.to/2MI0zN9

14 October 2019