Maria Aurora Couto “Filomena’s Journeys”

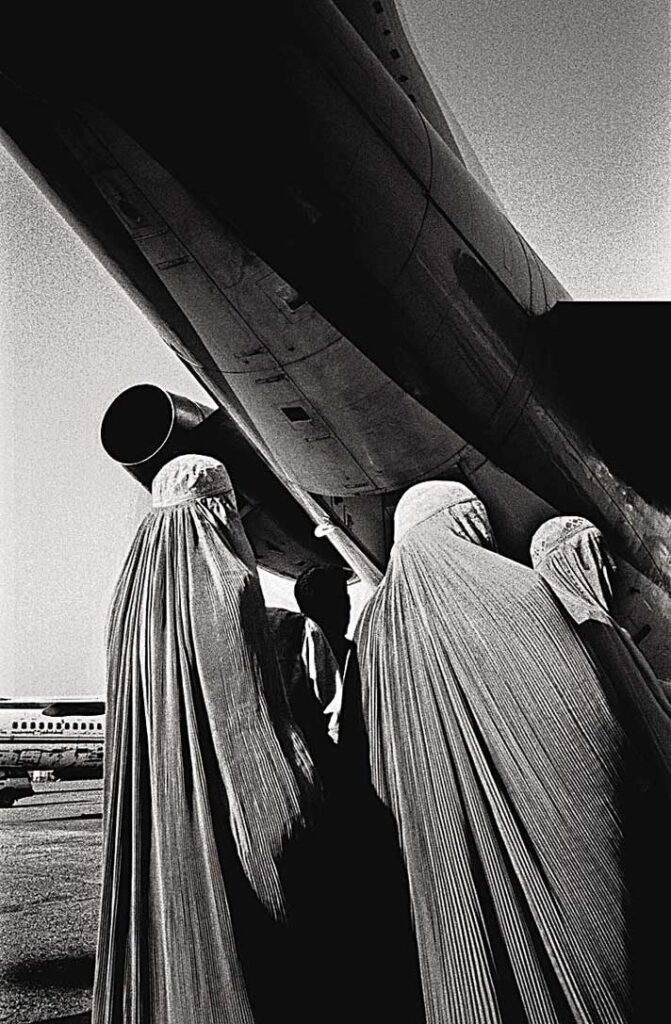

Filomena loved the house, and the company of her avo and sisters and the cook and maids. It was just that the strict discipline of indoor life, especially the indoor life expected of the women of her class, did not interest her very much. She would watch Avo and her elder sisters sitting upright for hours with their embroidery baskets, crochet needles and hairpins to produce fine lace, but she was restless, she disliked the stillness.

Filomena loved the house, and the company of her avo and sisters and the cook and maids. It was just that the strict discipline of indoor life, especially the indoor life expected of the women of her class, did not interest her very much. She would watch Avo and her elder sisters sitting upright for hours with their embroidery baskets, crochet needles and hairpins to produce fine lace, but she was restless, she disliked the stillness.

(p. 23 Filomena’s Journeys)

Filomena’s Journeys is about Maria Aurora Couto’s mother. It is a memoir that has been many years in the making. Filomena had a life that was not easy. She had been orphaned by the age of seven years old, married young, had seven children and had a fairly useless husband who ultimately abandoned the family.

Putting together a woman’s life is never an easy task, especially within a family. It is like a patchwork quilt. Pieces of the woman’s life need to put together skillfully to create a narrative. There is a narrative that dominates family lore; plus many other experiences and stories that create an image of the person. Much of the life that she leads disappears into a silence, but to create a narrative requires immense patience, hard work and the author has to be prepared for an emotional roller coaster since it may involve unearthing stories that are disconcerting, apart from ruffling the feathers of some relatives. For instance while writing this book Maria Aurora Couto discovered that her father had practically handed over the family home to his brother in the selection of lots; her mother had somehow rustled up the required three thousand rupees to retain the property but it was too late — the deed was done. Surprisingly, whenever the author wishes to refer to herself in the book, it is always in the third person. Yet not an unheard of literary technique. It helps provide a distance and a perspective to the narrative being constructed.

In Filomena’s Journeys Maria Couto weaves together biographical details with the socio-political and cultural context of Goa admirably. The memoir is reads like a story, peppered with facts and analysis about Goa under Portuguese rule and post-Independence.There are details about the structure of Goan society and the transformations, details about cooking, village life etc that are fascinating. It makes an excellent companion to Goa: A Daughter’s Story published over a decade ago.

When Filomena’s Journeys was published I had a posed a few questions to Maria Couto via email. Here are extracts from the conversation:

Which point of the book did you begin the manuscript with?

Very difficult to write and I gave up when trying to write in the first person. After some months, tried the third person narrative and that worked better. It helped to divide the book into four sections each devoted to a period in time, Began with imagining Filomena’s childhood, tragic loss of parents, support from strong women in the family, grandmother and aunt, the bedrock of faith, tradition in an agricultural community.

How many revisions did it undergo?

Countless revisions

How did you achieve the balance between fact and telling a good story, for it to be accessible?

It was not a conscious effort. Rewriting must have smoothed the narrative.

How many years in the making was it?

Three years. But as my closest friends tell me, I have talked about their lives, their society for years….TRYING to understand through conversation over years—Goan society rather than just my parents.

How has the family received it?

They are happy it has been so well received.

How did it, if at all, transform you as a writer and impact your relationship with your family?

We are very bonded, five sisters. So there has been discussion, argument and general acceptance of my narrative. Being the eldest, I have usually had my way!!

Did you have to dig deep in archives for historical facts or is this reconstructed from family documents and memory?

Much time spent with Portuguese newspapers—1900-50 of the first five decades . Some gazetteers, conversations with 70- and 80-year-olds from the villages of my parents, along with memories shared by members of the family.

Writing about women, especially ancestors, is never easy. They leave very little paper trails or even photo documentation. Much of the info of their lives is tucked into personal correspondence, cookbooks, and some photographs. Otherwise the impression that they leave in family lore. Many times reconstructing the real woman is tougher and at variance with what the subsequent generations recall. Did you also find it to be so?

No I did not because my mother’s life had such a strong impact on me—as the eldest, sharing and observing, it has been a questioning approach all my life. Trying to understand her modernity within a tradition which she respected and observed; within a faith that was so grounded in rigour at one level and yet so open to respect for all faith; her joy in life in the midst of unendurable experience—phenomenal.

Maria Aurora Couto Filomena’s Journeys: A portrait of a marriage, a family & a culture Aleph Book Company, New Delhi, 2013. Hb. pp. 290 Rs. 495

4 March 2014