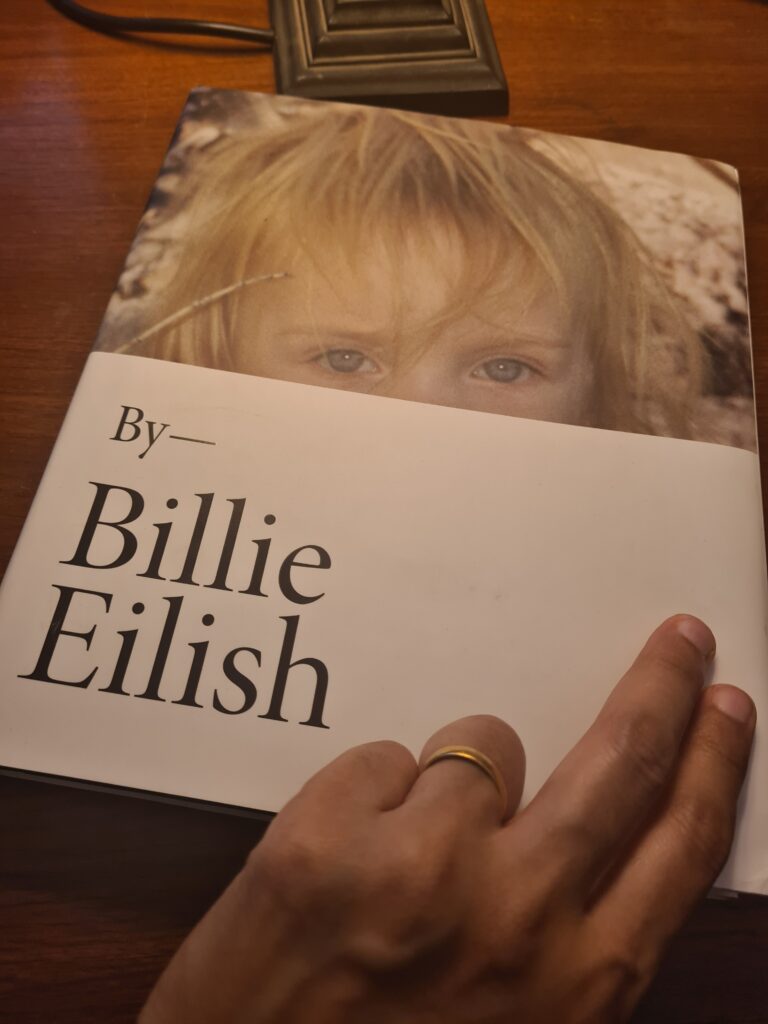

“Billie Eilish” by Billie Eilish

Billie Eilish started publishing music with her brother, Finneas, as a teenager. The duo is immensely popular. Billie Eilish is a multiple Grammy winner. She is 19. She has published her auto-biography called Billie Eilish. It is a photobook. It also shows stills from her music videos that she mostly directs herself. It is a photo-documentation of a pretty little baby to a superstar in less than two decades. She is young enough to have photo albums to browse through of her childhood and recall memories. Her dog that she rescued when Billie was six years old, is still living with her. Her parents and brother accompany the singer everywhere. Her father is an integral part of the crew. There are many photographs of her with her family and they do not seem to be posing for the sake of a family album memory. They are a team. It is evident.

Listening to her music is quite something. The words can be dark. But the arrangement is curious. It is a cross between performance poetry and recitation. The music tracks seem to have a life of their own too. The effect is enhanced when Billie Eilish is seen performing on stage or in her music videos wearing outrageously loud colours. It requires immense confidence about oneself to wear such bold colours. Musicians have been known to perform wearing dramatic costumes while performing in front of audiences, but there is something electric in the colours that Billie Eilish chooses, especially the fluorescent shades.

Some of her tracks like “Lovely” and “Bad Guy” have had 1.2 B and 1.1 billion views on YouTube, respectively. The combined views of two songs are nearly double the population of India! Her first song “Ocean Eyes’” (365 million views) sounds very much like Sam Smith. It was her first song. Her brother had written it for himself but realised that his younger sister did a better job at singing it. They recorded in their bedroom and uploaded it on SoundCloud. It went viral. In fact, the breakthrough achieved by many of the modern pop artists is phenomenal —whether it is Dua Lipa, Charlie Puth, Shawn Mendes, Arctic Monkeys, Justin Bieber, and Ed Sheeran. All of them have the common factor of using social media platforms to release their music. Once the tracks went viral, the record companies via their scouts signed them up. Billie has amassed over 54 million monthly listeners on the streaming service Spotify and over 50 million followers on Instagram. Her meteoric rise is similar to that of Liam Payne, One Direction, who at the age of fourteen years old also became a superstar and was banned from playing football in his own school field, as he had fans gawking at him from the boundary wall. He revealed this in a podcast with Steven Bartlett.

Eilish signed with Darkroom/Interscope in November 2016 just ahead of her fifteenth birthday. Darkroom/Interscope Records is the label for artists including Eminem, Madonna, Gwen Stefani, Imagine Dragons, Kendrick Lamar, Lady Gaga, Lana Del Rey, Maroon 5, Selena Gomez, and U2. It noticed this new young singer and snapped her up. A comment of Billie Eilish that stands out while negotiating and signing the contract was that no one knew how to talk to or direct a child, which is what she was, a fourteen-year-old. It is precisely why she took over the direction of her music videos. Apparently, she always uses real stunts. No special effects. It is admirable if you see some of the videos with the feathers sticking to her in the black goo. She sat through the make-up sessions.

She has mostly been home-schooled while her parents who were musicians also managed their professional commitments. Billi Eilish pours her heart and soul in her music and the videos accompanying it. Take for instance, the anime-inspired videos such as “You Should see me in a Crown”. It is a “creepy video” as my eleven-year-old daughter describes it, but it does not stop my daughter from listening to Billie Eilish’s music.

The self-confidence and assuredness of this young singer is quite something. It is evident even in the simple title of her book — Billie Eilish. It took Elton John, in his seventies, to entitle his memoir, Me. Billie Eilish has not even completed her second decade and her autobiography is Billie Eilish. In 2020 Eilish became the youngest artist ever to write and record a James Bond theme song. According to a Reuters article, she is quoted in clips of the audiobook as saying:

It’s funny like, I think a lot of people think that when Ocean Eyes’ came out, suddenly I was a superstar and quit everything and just became like famous… and it did not work like that at all… Yeah, my life stayed the same for a while. I was still dancing hours and hours and hours a day. And I was in choir still and I was doing all the same things I did. I was in circus class.

Listen to the track she released during the pandemic in Nov 2020. It is called, “No Time to Die”. It is the theme song to the forthcoming James Bond film with Daniel Craig. She credits Amy Winehouse for being a major influence on her music and yet this is a song that is soooo Billie Eilish. It cannot belong to anyone else! Read the photobook. It is a lovely documentation of a child/superstar born in the digital-informative-picture-rich age. Every step of her life seems to have been documented. It will be definitely popular with her fans and for those beyond who are curious about this popstar. The beautiful layout, with no expenses spared on the quality of production especially of the images, is a testament to the popularity of BillieEilish. The publishers will more than recover their cost in the making of this book and it will be well deserved. There are plenty of videos and images available online but there is magic in holding a print book consisting of stills. Billie Eilish exploits this old-world charm of browsing through images in hard copy, almost as if it is an invitation to view her family album and thus, gives her fans what they constantly desire – an intimate look into the singer’s life beyond the stage and recording studio. Very well done!

On 29 July 2021, Billie Eilish released her second album — Happier than Ever. It has met with praise from critics. Listen to it. Every track has its distinctive style. The words are astonishing as the young pop star has addressed her superstar status, the trolling she has faced, the titles of the track are very revealing too in terms of what she is feeling/experiencing. The musical arrangements are distinctive in every track. They do not merge into each other as a blur. The opening bars of “Halley’s Coment” begin with the piano chords sounding almost like the begining of a hymn. Curious that she should name a song after a comet that is known to appear periodically in the earth’s orbit and can be seen with the naked eye. Halley’s Comet’s claim to fame is the tail that it leaves in its wake, similar to other comets, except that this one is visible like a puff of cotton ball. Much of this analogy is applicable to Billie Eilish too with her phenomenal presence in the music world, sharp and illuminating, leaving an ephemeral trail of stardust in her wake.

The album’s tracks are characterised by her trademark whispering-style of singing. When she first burst upon the music scene, her songs tended to be indistinguishable from the popular artists of the day such as Sam Smith. Whereas in this album, most of the songs feel as if they hear hearkening back to a musical era with very distinct brands of music. The title track, “Happier than Before” feels like a song from the black-and-white film era. The choral arrangement in the opening of “Goldwing” sounds like traditional Church music. “Getting Older” has a rhythmic, gentle but firm beat that is much like the music one associates with Billie Eilish, yet has made me Thurberish with its strumming. There are examples of a range of musical styles in this album that do not make it dull. The titles leave one wanting to ask a million questions whereas the arrangement of the songs remain understated. In fact, this is exactly the feature that critics are pinpointing as being the reason for her fan base being underwhelmed. Yet, there is an addictive quality to the music. The lyrics continue to be dark, sombre and come with parental warning for their explicitness.

Hear the album. It is very good. Read the book too. It will help add a dimension to the singer.

Then watch the new BBC documentary called “Up Close” where she opened up about her frustration with trolls and internet criticism with the BBC’s Clara Amfo. “What is the point of trying to do good if people are just going to keep saying that you’re doing wrong,” Eilish tells Amfo. The film uses some of the images that appear in the photobook as well.

22 July 2021

Updated: 2 August 2021