Emma House, Deputy-CEO, Publishers Association UK, gave the following speech on 13 February 2018 at the 32 International Publishers Association Congress held at Hotel Taj, New Delhi. The congress was held in collaboration with the Federation of Indian publishers. Emma House’s speech has been published with her permission. The quotes are from the book — Publishers on Publishing — and statistics from Nielsen

WELCOME TO INDIA

For many of you this is your first time to India and although we are on Day 3 of the Congress I hope you will have got a good feel for what India has to offer beyond the world of Bollywood, Cricket and Curry.

For many of you this is your first time to India and although we are on Day 3 of the Congress I hope you will have got a good feel for what India has to offer beyond the world of Bollywood, Cricket and Curry.

I’m going to give you a quick run through of some of the publishing insight I feel visitors to India should know about.

Over the past few days you will have heard some impressive statistics about India which I can add to with further impressive figures about the publishing sector here.

India is the sixth largest economy in the world with a nominal GDP of $2.45 trillion.

India recently overtook China as the fastest growing large economy and is expected to jump up to rank fourth on the list by 2022.

India’s GDP is still highly dependent on agriculture (17%), compared to western countries. However, the services sector has picked up in recent years and now accounts for 57% of the GDP, while industry contributes 26%. India is very much moving towards a knowledge economy.

India has 22 official languages – English is one of them but Hindi is the most common. Marathi, Malyalam, Bengali, Telugu and Tamil languages also have a strong culture of reading.

PUBLISHERS on PUBLISHING: Inside India’s Book Business Edited by Nitasha Devasar is a new publication  specially developed for this congress and on sale here at the back of the room, and will provide everyone with valuable insights. Some of the information in my presentation comes from this book.

specially developed for this congress and on sale here at the back of the room, and will provide everyone with valuable insights. Some of the information in my presentation comes from this book.

The publishing industry in India has a long history which has really boomed in the last few decades. It is now behind only the US and UK, ranking 3rd in the world in English language publishing. Many successful Indian publishing companies are family run businesses passing through the generations. In the last 20 – 30 years however we have seen many multi-national publishers set up their Indian offices, firstly as joint ventures but over time becoming wholly owned subsidiaries.

For many years Foreign Direct Investment into India was limited, however this began to change with economic reform in the 1990s leading to real movement in journal publishing from around 2003. The market has opened up since then. We now see over 9000 publishers, in at least 16 languages other than English forming a colourful publishing industry which accommodates the multinationals, independent and family run enterprises publishing in the English and Indian languages. English language publishing in India stands at around 55 per cent of total publishing, 35 per cent is constituted by Hindi, and other Indian languages make up the remaining 15 per cent. The Book Market is estimated to be around 7 billion dollars dominated by academic and K-12 publishing, and important to note – consumer publishing forming only a small percentage of sales.

To give you a flavour of the types of consumer books which are popular in India.

By genre – Children’s Books, Romance and sagas, Crime Thrillers and literary fiction, Popular Psychology Mind, body and spirit as well as economic and management

BEST SELLING BOOKS 2017: From both imported titles with world famous names like Harry Potter, Dan Brown, John Green but also home grown Indian voices, many of whom have great standing on the international stage

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid – Book 12

- Dan Brown – Origin

- Turtles all the way down – John Green

- Harry Potter

- This is not your story – Savi Sharma

- I do what I do – Raghuram G Rajan

- The boy who loved turtles – Durjoy Datta

These impressive statistics about the population, the economic growth, the size of the publishing industry would all encourage those who look at India for the first time as a market destination for either publishing, selling rights or exporting books as a market of GREAT POTENTIAL.

- Population – 324 billion and growing

- Increased literacy rates

- Increased investment in education

- Fast growing middle class

- Much greater promotion of books and reading

However the industry faces many challenges, some common to us all, some unique to India:

- The size of the market is under-estimated with many book sales unrecorded due to sales through pavement news stands and smaller outlets

- A large number of publishers, especially in Indian languages do not use ISBNs

- The pricing model is squeezed in every direction from big increases in property prices and rentals as well as staff salaries, but importantly a challenging supply chain and distribution system which often sees high discounts and extended credit coupled with low levels of pricing and minimal increase in book prices. As a result it’s easier to make sales than make profitable sales, and to be paid promptly

- Piracy and photocopying is common place

Moving on to what I feel is an incredibly exciting feature about India which needs to be showcased – and that is Online retail. India is in a rare situation of having what The Hindu Business Line called in a recent headline “A two Horse Race In India – Flipkart Vs Amazon”.

First to the ecommerce market was Flipkart which began its life in 2007, founded by 2 ex-employees of Amazon with venture capital funding. Starting out with books, and addressing the nascent ecommerce market by introducing a cash on delivery model that is still used today, it’s been a turbulent journey for Flipkart, including a phase of when they faded out of the bookselling picture especially with Amazon entering the market. It has however managed to attract investment from Microsoft, Tencent and Ebay. Ten years on from it’s launch, in August 2017, Japanese internet giant SoftBank invested over $2.5 billion in Flipkart to become one of its largest shareholders, with rumours that Walmart could be its next significant investor.

Looking at the ebook market – this remains a small percentage of sales, hovering at around the 5% mark. Flipkart launched its ebook store in November 2012, however the ebooks catalogue was bought by Rakuten (Kobo) in 2015 and customers were transferred to the Kobo platform in recognition of the overwhelmingly dominant nature of the physical book market and Flipkart’s decision to focus on this strategic direction.

Amazon took its first step in the Indian market 5 years after Flipkart in 2012 when it launched Junglee.com, a site which allowed customers to compare prices online but not purchase items directly. At that time, Amazon was not allowed to stock and sell its own products due to Indian regulations preventing multi-brand retailers from selling directly to consumers online.

In June 2013 Amazon launched its marketplace selling books and video content – the model which is still in operation today. And in 2016 it made its move into publishing and purchased Westland (which was a major distributor but started publishing in 2007 and fast became one of the top five English language trade publishers in the country.

The two ecommerce giants now compete fiercely, not only in books, but notably in the mobile phone market. With a fast-growing market of smart phone users, the online market place in India is one which is amongst the fastest growing in the world – so we watch this race with keen interest.

The Book Culture in India

I take a quote from the publication I mentioned at the beginning from -Thomas Abraham, MD, Hachette India who says “There is a need to develop a book culture first and then the retail culture”.

Certainly here in India, the book culture is changing and growing. Firstly with a boom in bookstores across the country including major chains Crossword and Oxford Bookstores as well as fantastic independent bookstores. More recently however is the rise in popularity of literary festivals and book fairs. Anyone who has visited the Delhi World Book Fair or the Jaipur Literature Festival will have seen the hunger for and love of books that is being fostered here in India.

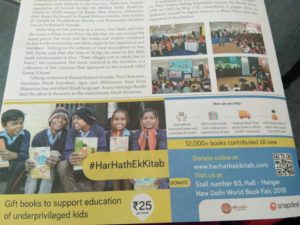

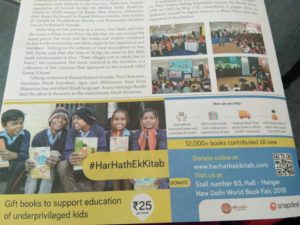

The National Book Trust of India also plays a major role in encouraging reading and literacy, and especially in the  more remote places in the country and can be commended for their campaign “Har haath, ek kitab” (one book in every hand), which is a nationwide online books donation drive especially targeting underprivileged children, and aims to build a reading habit among them.

more remote places in the country and can be commended for their campaign “Har haath, ek kitab” (one book in every hand), which is a nationwide online books donation drive especially targeting underprivileged children, and aims to build a reading habit among them.

General view all these things really have helped foster the reading culture and there is always more to do.

Self-publishing is increasing in popularity in India – Kindle Direct Publishing is now possible in a range of Indian languages as well as the emergence of a range of other self-publishing platforms.

Another issue which has been featured over the past few days is the matter of “Freedom to Publish”, a topic which is being hotly debated here in India. India which whilst being a fiercely democratic country has defamation laws, which make publishers, not just authors, subject to criminal prosecution. A section of India’s penal code criminalizes “deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.” Such acts, which the law says can be spoken or written, are punishable with up to three years imprisonment and fines.

This played out in a very public case in 2014 with a book by author Wendy Donniger The Hindus: An Alternative History, which was banned for its controversial content, following an extensive legal battle. This case and other similar cases have prompted huge concerns for Free Speech in India

Despite the challenges that the Indian publishing industry faces, there is much to be optimistic about. It’s certainly never a dull moment in this land of opportunity and I for one look forward to seeing how the market develops, how is continues to address the challenges and seize the vast opportunities to continue to build a book loving country that produces world leading content.

15 February 2018