Life after “The Clifton Chronicles”: An Interview with Lord Archer

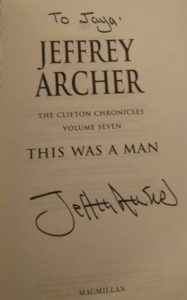

( My interview with popular writer Jeffrey Archer was published on literary website Bookwitty on 6 February 2017. The Clifton Chronicles are published in India by PanMacmillan India. )

( My interview with popular writer Jeffrey Archer was published on literary website Bookwitty on 6 February 2017. The Clifton Chronicles are published in India by PanMacmillan India. )

While reading the Clifton series, I could not help but draw comparisons between Charles Dickens and Jeffrey Archer as extraordinarily popular authors of their times. Later I discovered that in an an interview Lord Archer acknowledged Dickens as one of his literary heroes. Each portrays characters embedded deeply in socio-economic divisions, while creating an atmosphere with their language, expressions and manner of engagement. Unlike in literary fiction, where much of the time is spent detailing dress and manners and manner of accents, The Clifton Chronicles focus on how to operate within specific socio-economic divisions. There is a nuanced reflection of what society was like. The character building does not happen much with authorial intervention, with long expositions about an individual, but is achieved through their engagement with the surroundings. The way Lord Archer captures the manners and speech reflecting the class of an individual may not be something to mention in polite society, but it is most certainly a discreet cultural language everyone is acutely aware of.

Dickens may be very popular now and is the darling of academics worldwide, but soon after his death he was not much talked about. It was a while after his death, probably in the early 20th century, when it became fashionable to read and discuss him. Similarly, with Lord Archer’s novels there is a very deep silence amongst the literary establishment that exists in acknowledging him as a storyteller (in fact he makes some astute observations on the big literary fiction prizes in these novels). Surely commercial fiction like his has a reason to exist? Certainly the numbers of units sold worldwide, including in India, tell a pretty good story too – it is the kind of success literary fiction writers aspire to. So this deep distaste for popular literature is unfathomable? Probably the classical divide between “high” and “low” art continues to be deeply entrenched. Hence popular fiction like The Clifton Chronicles is seldom considered for literary prizes.

On finishing the series I corresponded with Lord Archer, facilitated kindly by his publishers, Pan MacMillan India. Below are edited excerpts of our correspondence.

Before you began writing The Clifton Chronicles did you broadly plot out a series arc?

No, initially I envisioned only three books, then five, but as I wrote, the characters grew and changed, and I needed to keep going in order to get them to where I wanted the saga to end. I rarely map out the whole plot of a book, although I do always have an idea of how I want it to end – though it sometimes takes a different direction half-way through!

Dickens and you serialised stories – he in Household Words and you with The Clifton Chronicles novels. Both have had the effect of keeping readers waiting in great anticipation for the next instalment. Why did you choose to write a series and not a single fat doorstop of a novel chronicling the Clifton and Barrington saga?

I looked on this as a new challenge as I’d never written a series before.

Creating and sustaining the plot for 3000 pages spread over so many decades must have required tremendous research and fact-checking. How did you do it? Do you work with a team of people?

I don’t have a team of people – I read a lot beforehand, and I have a researcher who helps me with some background research, and along the way I will speak to different experts in their fields if I’m writing about a particular subject or place for example.

How often do you revise your manuscripts?

I will write out a chapter maybe three times during the first draft, and then when my PA has typed up my handwritten pages, I’ll then work on them for several more drafts. I then discuss this with my editor and revise it again. So it could be revised a dozen times.

How do you name your characters? (There are so many!)

I’m always looking for new names to use – I might be watching TV and as the film credits roll, think ah, that surname is interesting, or be reading a newspaper and spot a name I haven’t used before which would suit a particular character. They could come from anywhere – I think I may even have used a couple of names from my local rugby team.

You have been publishing for more than four decades now. What are the transformations in this industry that you have witnessed?

The biggest change is of course the incredible rise in eBooks. But I think this has only changed the industry for the better – encouraging more people to read.

Have these in any way affected your style of storytelling and its productivity? How has it in particular affected the author-reader relationship? Has the demographic of your reader changed or remained constant?

My readership has grown with The Clifton Chronicles, and my fans might be 9 or 90!

Many claim your books to be inspirational for their stories of triumph, yet you portray society as it is. It makes me wonder if these books are semi-autobiographical. Are they?

Some of the characters and the events within The Clifton Chronicles series are certainly inspired by my own life and even people I knew. I was brought up in the West Country of England, so have always wanted to set a novel in that area. There is a little bit of me in Harry Clifton – we’re both authors for a start, and certainly Emma was based on my wife Mary.

Who is your favourite character in the book?

Lady Virginia, without a doubt. She turned into a fan favourite. I was going to kill her off after book three, but she demanded to continue!

What kind of books do you like to read?

I read many different genres including biographies and non-fiction for research, but my favourite is fiction, from the likes of Dickens, Dumas, H H Munro and Stefan Zweig.

Will you have these books optioned for a period drama?

I would love to see The Clifton Chronicles as a TV drama series.

What next after The Clifton Chronicles?

I have a new book of short stories coming out this year, and am currently working on my new novel.

7 February 2017