Scholastic Encyclopaedia Of Dinosaurs

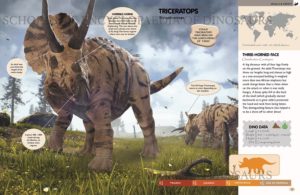

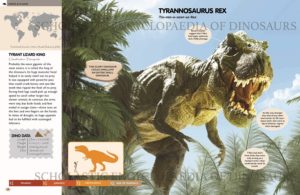

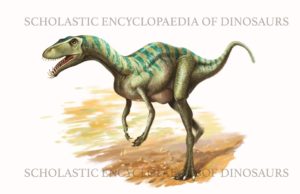

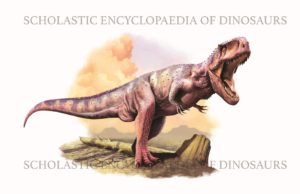

Scholastic Encyclopaedia Of Dinosaurs is a visual delight apart from beingpacked with information. The well-recognised dinosaurs such as Triceratops ( Three-horned face), Mamenchisaurus, Kentrosaurus ( Spiked Lizard) and Tyrannosaurus Rex ( Tyrant Lizard King) are described beautifully. There are full-page colour spreads with exciting information about each highlighted in a comment bubble within the illustration. Alongside it is an illustration in a box comparing the height of a human being to that of the dinosaur. Neatly presented in a panel on the side is the geographical location of the dinosaur, in which year were the fossils first discovered, dimensions of the animal, and its diet. Without it being too much of an information overload, details about the dinosaurs are presented so clearly with simple visual layouts and a clean font used that even I for the first time in years has finally understood in one fell swoop what Trynnosaurus Rex is all about. It is utterly brilliant.

Scholastic Encyclopaedia Of Dinosaurs is a visual delight apart from beingpacked with information. The well-recognised dinosaurs such as Triceratops ( Three-horned face), Mamenchisaurus, Kentrosaurus ( Spiked Lizard) and Tyrannosaurus Rex ( Tyrant Lizard King) are described beautifully. There are full-page colour spreads with exciting information about each highlighted in a comment bubble within the illustration. Alongside it is an illustration in a box comparing the height of a human being to that of the dinosaur. Neatly presented in a panel on the side is the geographical location of the dinosaur, in which year were the fossils first discovered, dimensions of the animal, and its diet. Without it being too much of an information overload, details about the dinosaurs are presented so clearly with simple visual layouts and a clean font used that even I for the first time in years has finally understood in one fell swoop what Trynnosaurus Rex is all about. It is utterly brilliant.

Tyrannosaurus Rex

Dinosaur books exist by truck loads in the market. A significant proportion of storybooks for children particularly for pre-schoolers rely upon dinosaurs. Many times they are anthropomorphised. The dinosaurs often used are Trynnosaurus Rex and Mamenchisaurus, so much so these complicated names come tripping off the tongues of tiddlers. Most of the dinosaurs children are familiar with are found in USA, Europe and China.

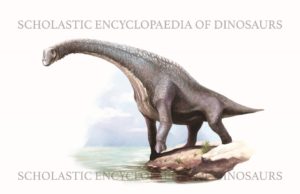

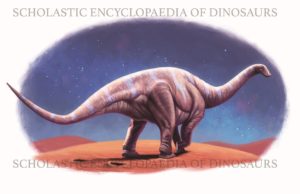

This is where the Scholastic Encyclopaedia Of Dinosaurs is exceptional. It has mentioned the few dinosaurs found in India like Titanosaurus Indicus, Kotasaurus, Laevisuchus Indicus, Rajasaurus Narmadensis, and Therizinosaurus. What is truly astonishing is that these dinosaurs were drawn by Krishna Bala Shenoi based on the evidence available.

The editors and illustrator did try and search for illustrations that may have existed based on the skeletal remains discovered except that no satisfactorily clear images were to be found. This is what the illustrator Krishna Bala Shenoi had to say about the process:

Indian dinosaurs haven’t been represented in a plethora of paleoart or scientific reconstructions in the way that most commonly known dinosaurs have been, for a variety of reasons. The references I had to work with (some given to me, some discovered online) were so few in number, so lacking in detail and, most significantly, so contradictory between themselves that I had to do a lot of fairly unscientific guesswork.

My process came down to collecting the images I could, constructing a notion of the dinosaur that sort of fit the multiple references, and then filling in the blanks with details from similar dinosaurs that had richer libraries of visual resources. In one case, I used images of a toy dinosaur (different from the one I was illustrating) as a springboard for the construction of the dinosaur’s body.

I was initially very reluctant with every move I made, fearing I was way off the mark, but later discovered how wrong paleoart has been over the years. That was comforting in a way; it gave me permission to be okay with, essentially, making some details up. So I just had fun with it.

I illustrate digitally, but there’s a misconception that that means it’s not hand drawn. It very much is. I work on a device called a graphic tablet which ports my drawing/painting from the tablet surface onto my computer screen in real time.

This is an extraordinary achievement and is a testament to how much effort the editorial team is willing to put in to make available authentic information in a stunning layout.

This is a book for keeps. To be read. To be shared. To be bought for reference, libraries and school resource materials.

To be gifted liberally simply for the pleasure of holding and reading a beautiful book.

Scholastic Encyclopaedia Of Dinosaurs Scholastic India, Gurgaon, India, 2018. Pb. pp. 80. Rs 399

Reading level: 9 – 16

30 May 2018