UNESCO World Heritage Sites of India Series

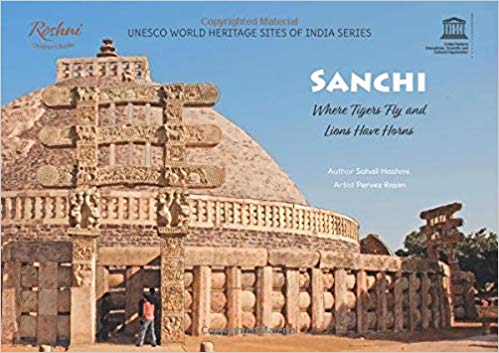

Mapin Publishing and UNESCO have co-published a set of five picture books called UNESCO World Heritage Sites of India Series. These books have been published with the support of Parag, an initiative of TATA Trusts. The five sites described are — Mahabalipuram, Sanchi, Keoladeo Bird Sanctuary, Qutb Minar, and Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. There are 37 World Heritage Sites in India of which 29 are cultural and 8 are natural sites.

There is a separate author and illustrator for every book while the series editor is historian Narayani Gupta. In fact Prof. Gupta has written at least two other books for children. One was on Delhi and the second on Humayun’s Tomb. Launching this series is a good attempt at making information about historical sites accessible to children. These are also reasonably priced at Rs 195 each so the parents too get “value for money” in terms of information, text, pictures and some exercises at the back of every book.

Of the five books, the ones on Sanchi and Qutb Minar are best told. Sohail Hashmi’s Sanchi: Where Tigers Fly and Lions Have Horns manages to delve immediately into the historic site giving a fabulous description of the gates, sufficient amounts of historical context and involving the children in the story, thereby incorporating their perspectives too. For instance, the children spot holes in the walls that are visible to them as it is at their eye level. Something that an adult could have possibly missed. So the guide/Sohail Hashmi immediately points out that these are probably newly drilled holes to assist in draining rain water from the complex and help protect the monument. Narayani Gupta’s Qutb Minar is also beautifully written describing the complex while focussed on the Qutb Minar, its complicated history and the do’s and dont’s children should observe while visiting the historical site. For instance the chowkidar warns the children not to play on the graves warning them that the ghosts would come and haunt the children. A playful account in the story but an acute observation to include as children are wont to all sorts of pranks in open spaces and could do with learning a few rules of etiquette to observe while visiting historical monuments.

Compared to the aforementioned books, the remaining three titles — Keoladeo Bird Sanctuary: The Kingdom of Birds, Mahabalipuram and Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus: Travelling Through Time are not as elegantly written, illustrated or produced. For example, Keoladeo Bird Sanctuary: The Kingdom of Birds while giving the history of the Bharatpur bird sanctuary as it is popularly known is an annoying book to read. Firstly, if it is meant for children it has far too many dark illustrations making it impossible to identify the birds clearly nor read their names that have been printed in black on a dark background! Secondly, the editing is sloppy. It is inexplicable why certain sentences from the text have been put in bold or made in a larger font when there is nothing significant in them. Also if these are meant to be edutainment books then surely a little more care could have been spent on details such as the meal the children in the story ate. “Everyone was careful not to spill any food and no plastic or paper was left behind.” Surely in a book that is focused on environmental conservation a little thought could have been spent in discouraging the use of plastic. Instead of cleaning up the plastic used, point out that no plastic was used, only biodegradable or reusable plates and glasses were used. Even 94-year-ol David Attenborough speaking at Glastonbury 2019 spoke about the effect of plastic on the planet. No effort can be small enough. Readers, especially young, pick up cues from books and imitate behavioural patterns.

Finally, why are there two illustrations each of the Grey Hornbill and Painted Stork instead of using the resources available to accommodate more bird pictures? Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus: Travelling Through Time is no better either. It is inexplicable why the device of time travel had to be introduced in a story about a historically rich site such as this railway terminus built in the nineteenth century. Introducing the element of time travel merely weakens the storytelling for it begins to pull the narrative in different directions. It is also equally baffling why there is a glossing over of historical facts such as mentioning in the story that Victoria Terminus was renamed in 1996 to Shivaji Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. It happened in recent memory. It is mentioned in the inner front flap as being called Victoria Terminus for at the time India was governed by the British. So why not say explicitly that renaming the terminus in the fin de siecle was also politically motivated? Shouldn’t children be made aware of history rather than a selective narrative? Mahabalipuram is also disappointing for its insipid storytelling and bland illustrations.

Perhaps the series would have been on a stronger footing if editorial guidelines had been set for all the contributors. Also a template design created to ensure that there is some consistency in the book production. It can be creatively debilitating to adhere to a template design but at times these tough decisions need to be taken particularly when catering to young readers. Children seek familiar markers. For instance choose whether boxes will be used to highlight information ( as is in Qutab Minar ) or pull out quotes ( as in Keoladeo Bird Sanctuary). Secondly, it is a good idea to use multiple illustrators but give them firm guidelines that the pictures while being aesthetically appealing also need to be informative so create them with a child’s perspective in mind, not an adult’s. Thirdly, if these are books meant to focus on the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in India then the date when the particular site was designated so should be placed in exactly the same spot in every title. This is not the case. Only Mahabalipuram and Keolodeo mention the dates in the box provided in the inner front flap of the books. Finally the awkward dimensions of the picture books make them go flippty-flop in an adult’s hands. For tinier hands this can only become cumbersome. So it will not be surprising if children abandon the books rapidly. This size of the book is definitely not child friendly.

Ultimately this is a good idea as a book series for younger readers except that it has been shoddily executed. Perhaps the team would have benefitted well by creating stories of the same standard as that created by Sohail Hashmi and Narayani Gupta. Who knows, maybe future titles in the series will consider it?

Updated on 1 July 2019 to embed the David Attenborough link.

29 June 2019