Lister came to the vital realization that he couldn’t prevent a wound from having contact with germs in the atmosphere. So he turned his attention to finding a means of destroying microorganisms within the wound itself, before infection could set in. Pasteur had conducted a number of experiments that demonstrated that germs could be destroyed in three ways: by heat, by filtration, or by antiseptics. Lister ruled out the first two because neither were applicable to the treatment of wounds. Instead, he focused on finding the most effective antiseptic for killing germs without causing injury: When I read Pasteur’s article, I said to myself: just as we can destroy lice on the nit-filled head of a child by applying a poison that causes a lesion to the scalp, so I believe that we can apply to a patient’s wounds toxic products that will destroy the bacteria without harming the soft parts of this tissue.”

Lister came to the vital realization that he couldn’t prevent a wound from having contact with germs in the atmosphere. So he turned his attention to finding a means of destroying microorganisms within the wound itself, before infection could set in. Pasteur had conducted a number of experiments that demonstrated that germs could be destroyed in three ways: by heat, by filtration, or by antiseptics. Lister ruled out the first two because neither were applicable to the treatment of wounds. Instead, he focused on finding the most effective antiseptic for killing germs without causing injury: When I read Pasteur’s article, I said to myself: just as we can destroy lice on the nit-filled head of a child by applying a poison that causes a lesion to the scalp, so I believe that we can apply to a patient’s wounds toxic products that will destroy the bacteria without harming the soft parts of this tissue.”

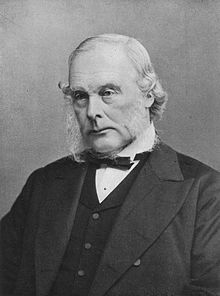

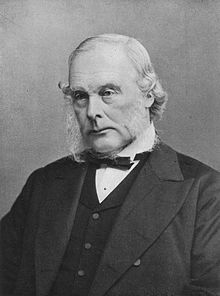

British surgeon Joseph Lister ( 5 April 1827 – 10 February 1912) was a pioneer of antiseptic surgery. He was born in a devout Quaker family. Simplicity was the Quaker way of life. Lister was not allowed to hunt, participate in sports, or attend the theater. “Life was a gift to be employed in honoring God and helping one’s neighbor, not in the pursuit of frivolities. Because of this, many Quakers turned to scientific endeavors, one of the few past times allowed by their faith.” His father, Joseph Jackson Lister, managed  the centuries old family business of being wine merchants but it was his discovery of the achromatic lens to eliminate the distracting halo in the compound microscope that earned him worldwide fame. This lens was showcased in 1830. His son, Joseph Lister, grew up in such a home where the spirit of inquiry was encouraged as was exploring miniature worlds with the microscope.

the centuries old family business of being wine merchants but it was his discovery of the achromatic lens to eliminate the distracting halo in the compound microscope that earned him worldwide fame. This lens was showcased in 1830. His son, Joseph Lister, grew up in such a home where the spirit of inquiry was encouraged as was exploring miniature worlds with the microscope.

The very first time he looked down the barrel of a microscope, Lister marveled at the intricate world that had previously been hidden from his sight. He delighted in the fact that the objects he could observe under the magnifying lens were seemingly infinite. Once, he plucked a shrimp from the sea and watched in awe at “the heart beating very rapidly” and “the aorta pulsating.” He noticed how the blood slowly circulated through the surface of the limbs and over the back of the heart as the creature wriggled under his gaze.

Yet Lister’s decision to become a surgeon was met with surprise by his family as it was a job that involved physically intervening in God’s handiwork.

And surgery, in particular, carried with a certain social stigma even for those outside the Quaker community. The surgeon was very much viewed as a manual laborer who used his hands to make his living, much like a key cutter or plumber of today. Nothing better demonstrated the inferiority of surgeons than their relative poverty. Before 1848, no major hospital had a salaried surgeon on its staff, and most surgeons ( with the exception of a notable few) made very little money from their private practices.

Lister had an insatiable curiosity about the world and was forever creating slides to view under his microscope. Later in Edinburgh he would convert a portion of his study at home into a laboratory where there were always perched tubes filled with different materials, plugged with balls of cotton. Next to it would be his microscope and slides he made. He was also a proficient artist — a skill that would help him document in startling detail his observations made during his medical career. Yet all through his life Lister also battled depression, a “garment of darkness”, which would often descend upon him. Despite these odds he would work in the hospital and later return home to do his research. Many would marvel at his dedication and diligence.

The early training to use a microscope was to stand Joseph Lister in good stead throughout his career as he pondered over the crucial question as to why wounds that were open inevitably festered and proved fatal for the patient whereas internal injuries such as broken bones healed and the patient recovered normally. Years later his supervisor would recall that while working together at the University College Hospital in 1851, Lister “had a better microscope than any man in college”. It was the microscope that would eventually help Lister unlock the medical mystery that had been plaguing his profession for centuries. This was at a time in the nineteenth century when surgeons believed pus was a natural part of the healing process rather than a sinister sign of sepsis, so most deaths were due to postoperative infections. Operation theaters were gateways to death. Infections were frequent in hospitals. They were filthy institutions as exemplified by an anecdote where a patient lay on a hospital bed completely unaware that the mushrooms growing on his damp bed sheet was not normal. The four major infections to plague hospitals in the nineteenth century were erysipelas or St. Anthony’s Fire ( an acute skin infection which turned the skin bright red and shiny), hospital gangrene ( ulcers that lead to decay of flesh, muscle, and bone), septicemia ( blood poisoning), and pyemia ( development of pus-filled abscesses). the increase in infection and suppuration brought on by the “big four” later became known as hospitalism.

The best that can be said about Victorian hospitals is that they were a slight improvement over their Georgian predecessors. That’s hardly a ringing endorsement when one considers that a hospital’s “Chief Bug-Catcher” — whose job it was to rid the mattresses of lice—was paid more than its surgeons.

Nineteenth century doctors had multiple theories for why infections occurred although they were clueless about how infectious diseases spread. Many surgeons believed pus was a natural part of the healing process rather than a sinister sign of sepsis. Another theory was that patients were infected by miasma arising from corrupt wounds. Between the 1850s and 1860s there was a shift from miasma being the root cause of infections towards contagion theories. Some doctors believed that contagious diseases were transmitted via a chemical or even small “invisible bullets”. Others thought it might be transmitted via an “animalcule”, a catchall term for small organisms.

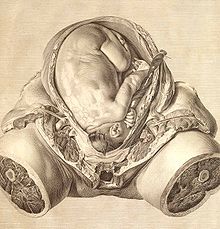

The Butchering Art’s graphic descriptions of surgical procedures in nineteenth century are horrific. They were a spectacle with the surgery taking place in a theatre packed to the gills mostly with students, physicians and few curious onlookers. Most surgeries before the discovery of choloroform were conducted with the patient wide awake through the painful procedure. The crude surgical instruments used were by today’s standards basic such as a saw. ( See image) Unfortunately most patients died in post-operative care inevitable due to infection setting in. Popular belief held it was due to the bad air in the vicinity of patient resulting in infection and ultimately death.

With the discovery of chloroform by the Scottish obstetrician James Y. Simpson and advent of anesthesia in 1846 the number of operations increased as surgeons were more comfortable operating knowing that their patients would no longer feel the pain of the knife cutting through them. Although hospitals in Victorian England were being rebuilt with more wards the high rate of mortality continued to grow as number of patients also increased and it became near impossible to keep hospitals clean and contain the infections. Primarily also because infection control was unheard of and hospitals were known by the public as “Houses of Death”. In Victorian England population also grew dramatically from one million to over six million with at times more than thirty people living in one room. There was dirt and filth with absolute no sense of public hygiene; infections were bound to spread.

as surgeons were more comfortable operating knowing that their patients would no longer feel the pain of the knife cutting through them. Although hospitals in Victorian England were being rebuilt with more wards the high rate of mortality continued to grow as number of patients also increased and it became near impossible to keep hospitals clean and contain the infections. Primarily also because infection control was unheard of and hospitals were known by the public as “Houses of Death”. In Victorian England population also grew dramatically from one million to over six million with at times more than thirty people living in one room. There was dirt and filth with absolute no sense of public hygiene; infections were bound to spread.

Completing his education in London, Lister moved to Edinburgh, the city which had established itself as the city of surgery. He went to work with Professor James Syme, surgeon at Edinburgh’s Royal Infirmary. Syme’s colleagues called him “the Napoleon of Surgery”. He was lightning fast as was his equally legendary cousin in London, Robert Liston, whose surgeries too Lister had witnessed. In fact Liston designed an amputation knife with a blade fourteen inches long and and a quarter inches wide. The dagger’s point, the last two inches of which were razor-sharp, was created to cut through the skin, thick muscles, tendons, and tissues of the thigh with a single slice. The “Liston knife” was Jack the Ripper’s weapon of choice for gutting his victims when he went on his killing spree in 1888.

While working in Edinburgh Lister realized his patients continued to die due to hospitalism. Frustrated Lister began taking tissue samples of his patients to study under the lens of his microscope so he could better understand what was happening at the cellular level. He was determined to understand the mechanisms behind inflammation trying to figure out the connection between inflammation and hospital gangrene. He and other surgeons tried many “solutions” such as using vellum to cover the wound to control inflammation and “water dressings” or wet bandages which they believed counteracted the heat of inflammation by keeping the wound cool. But there was no consensus as to why this occurred in the first place.

In the 1860s Lister was convinced cleanliness would help reduce mortality rates in hospitals due to hospitalism. Prior to this three doctors — Scotsman Alexander Gordon ( 1789), American essayist Oliver Wendell Holmes ( 1843) and Ignaz Semmelweis in Vienna (1847) — had tried making a similar connection between transmission of morbid substances from doctor to patient. Lister was so obsessed by this puzzle that his house surgeon said of him that a “divine discontent” possessed him.

His mind, he said, “worked ceaselessly in an effort to see clearly the nature of the problem to be solved.” Lister’s exasperation spilled over into the classroom, where he turned to his students with the question that had been haunting him for some time: “It is a common observation that, when some injury is received without the skin being broken, the patient inevitably recovers and that without any severe illness. On the other hand trouble of the gravest kind is always apt to follow, even in trivial injuries, when a wound of the skin is present. How is this? The man who is able to explain this problem will gain undying fame.”

It was the behest of his colleague and chemistry professor, Thomas Anderson, that Lister became familiar with the research on fermentation and putrefaction of French microbiologist and chemist Louis Pasteur. Upon reading Pasteur’s publications on the decomposition of organic material Lister began replicating the French scientist’s experiments in his laboratory at home. Pasteur’s experiments confirmed that fermentation was a biological process and that the yeast that helped produce wine was a living organism. His experiments established what is now considered a cornerstone of biology: Only life begets life. Soon the word “germ” was being used to describe these protean microbes. Pasteur began making the connection between putrefaction and fermentation as he was convinced both processes were caused by the growth of minute microorganisms. Lister too was now of the opinion that it was not the air as such but its constituent of microbial life that was the source of hospital infection.

Lister came to the vital realization that he couldn’t prevent a wound from having contact with germs in the atmosphere. So he turned his attention to finding a means of destroying microorganisms within the wound itself, before infection could set in. Pasteur had conducted a number of experiments that demonstrated that germs could be destroyed in three ways: by heat, by filtration, or by antiseptics. Lister ruled out the first two since neither were applicable to the treatment of wounds. Instead he focused on finding the most effective antiseptic for killing germs without causing further injury.

Many substances considered to be antiseptic such as wine, quinine, iodine and turpentine, had proved ineffective or caused further damage to the tissue, making the wound vulnerable to infection. Lister tried many solutions including the popular Condy’s fluid or potassium permanganate. None worked. Then Lister remembered reading that engineers at a sewage works in Carlisle had used carbolic acid to counteract the smell of rotting garbage and to render odorless nearby pastures that were irrigated with liquid waste. An unexpected benefit of the carbolic acid was that it also killed the protozoan parasites that had caused outbreaks of cattle plague in the livestock that grazed in these fields. Carbolic acid, also known as phenol, is a derivative of coal tar and was first discovered in 1834. Lister obtained samples of crude acid and observed its properties under the microscope. Soon he began experimenting with it on his patients but realized he needed to be a little more disciplined and methodical in his approach. So after a few trials he suspended using carbolic acid as a disinfectant for wounds in hospitals and waited for a patient with a compound fracture to show up.

…compound fractures [are] injuries in which splintered bone lacerated the skin. This particular kind of break had a high rate of infection and frequently led to amputation. From an ethical standpoint, testing carbolic acid on compound fractures was sound. If the antiseptic failed, the leg could still be amputated — something that would have likely occurred anyway. But if the carbolic acid worked, then the parent’s limb would be saved.

In early August 1865 Lister had the opportunity to work upon the compound fracture of eleven-year-old James Greenlees whose leg had been crushed by a the metal-rimmed wheels of a cart. Lister tended to the wound by creating a space in the putty cast in to which he poured carbolic acid. He looked after the boy himself for the next few days. After the initial few days inflammation began to set in and no amount of diluted carbolic acid could stem the redness. It was then Lister created a new solution of carbolic acid with olive oil. It worked. Six weeks and two days after the cart had shattered his lower leg, James Greenlees walked out of the Royal Infirmary.

Although Lister was evangelical about antiseptic methods there were few adopters of this method. In fact his critics were greater in number and began to write even in respected medical journals like The Lancet. For a while Lister was caught in a terrible wrangle with his contemporaries about the benefits of using antiseptics and it was proving impossible for hospitals to consider using carbolic acid despite statistics proving the dramatic fall of mortality rates in which Lister had enforced antiseptics be used. That is until 4 September 1871 when Lister was summoned to Balmoral Castle to attend to Queen Victoria who was gravelly ill with an abscess in her armpit that had grown to the size of an orange. Lister chose to lance the boil and used carbolic spray to disinfect the room. The next day when he came to dress the wound he realized that pus was forming once more. He needed to quickly stem the spread of infection. Spotting the atomizer he removed the rubber tubing of the apparatus, soaked it overnight in carbolic acid, and inserted it into the wound the following morning in order to drain the pus. It worked. Queen Victoria recovered.

With the royal stamp of approval to Lister’s antiseptic system the surgeon’s fame spread far and wide. His methods were accepted as far as in London. In 1876 Joseph Lister was invited to defend his methods at the International Medical Congress in Philadelphia. The American tour was a success. It also resulted in spreading awareness as well as popularizing personal hygiene products. One of these was Listerine invented by Dr. Joseph Joshua Lawrence in 1879 who had attended Lister’s lecture in Philadelphia, “which inspired him to begin manufacturing his own antiseptic concoction in the back of an old cigar factory in St. Louis shortly thereafter. ” Other products that sprang up were carbolic soap and toothpaste. Astonishingly one of the most surprising offshoots of this tour was the establishment of a corporation recognizable even today — Johnson & Johnson. Robert Wood Johnson upon hearing Lister speak joined forces with his two brothers, James and Edward, and founded a company to manufacture the first sterile surgical dressings and sutures mass-produced according to Lister’s methods. Lister died in 1912 after having been knighted by Queen Victoria and winning many other awards and recognition for his work.

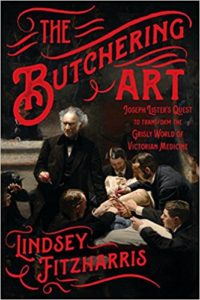

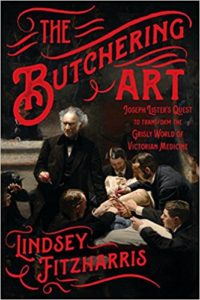

Dr. Lindsay Fitzharris who received her doctorate in the history of medicine, science and technology from the University of Oxford embarked upon educating and engaging with the public during her post-doctoral research. She was fatigued by academia and tenure-track and was far more keen to maintain her blog The Chirurgeons Apprentice and later her videos — Under the Knife .

The Butchering Art is a fantastic history of surgery in the Victorian Age. It is a perfect balance between facts and storytelling without making the subject dull. Dr Fitzharris’s love for the subject shines through. She uses the methodology and discipline of writing academic works in presenting a highly technical subject for the lay reader. The text is well annotated with end notes for every single chapter but not disturbing the design of every page. In fact she has been accused of “bastardizing” the discipline. To which she replies:

I think there is a misconception that writing popular history is easier than writing academic history. Both have their challenges, and just because a person can write one doesn’t necessarily mean that same person can write the other. I’m a storyteller first and foremost, and an historian second. I don’t apologize for this. Unfortunately, some academics don’t see a value in what I do. But the past doesn’t belong to scholars alone. It belongs to everyone. My hope is that I can bridge the gap between academia and popular history, and open up new and interesting subjects to a curious public.

( History of Science Society @Work interview with Dr Lindsey Fitzharris, April 2018)

Even though some of the academics may be disapproving of her style of making the history of medicine available, Dr. Fitzharris has won the 2018 PEN/E.O. Wilson Prize for Literary Science Writing and has been shortlisted for the 2018 Wellcome Book Prize. The Butchering Art was also featured in the Top 10 Science Book of Fall 2017, Publishers Weekly and the Best History Book of 2017, The Guardian.

Undoubtedly The Butchering Art is not for the faint-hearted for its gory descriptions of Victorian hospitals, operation theatres and death houses. Nevertheless it is an unusual page-turner for it is purely about scientific progress in Victorian England and the remarkable discovery of Joseph Lister.

Lindsey Fitzharris The Butchering Art Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books, Penguin Random House, UK, 2017. Hb. pp.

25 April 2018

And then there it is, our new, terrible silent routine. And to top it off, I have no birds and the world feels like a different kind of dark than it felt before. Mom isn’t perfect, but I miss her. I miss her picky neatness, I miss her bothering me about taking my nose out of a book and making a friend for once, I miss her getting on my case about my hair. I miss telling her about what I’m reading, what I’m thinking, asking her about work, listening to her carry on about Aunt Joan and whatever drama she’s gotten into. I miss her. There is a sadness I can’t shake, that’s not just from breakfast. There are no birds by the feeder. There aren’t pigeons cluttering the sidewalk as I go to school. I know, now, that last night’s dream was the last flight I’ll take.

And then there it is, our new, terrible silent routine. And to top it off, I have no birds and the world feels like a different kind of dark than it felt before. Mom isn’t perfect, but I miss her. I miss her picky neatness, I miss her bothering me about taking my nose out of a book and making a friend for once, I miss her getting on my case about my hair. I miss telling her about what I’m reading, what I’m thinking, asking her about work, listening to her carry on about Aunt Joan and whatever drama she’s gotten into. I miss her. There is a sadness I can’t shake, that’s not just from breakfast. There are no birds by the feeder. There aren’t pigeons cluttering the sidewalk as I go to school. I know, now, that last night’s dream was the last flight I’ll take.  Partition and Madness)

Partition and Madness) Writing about a teenager whose mental health is being questioned by everyone around her even though the teenager herself is under the impression that her reality makes perfect sense is probably not easy. Yet Sarah Moon’s undeniable wizardry is evident in her sensitive storytelling. Sparrow can be challenging even for an experienced author

Writing about a teenager whose mental health is being questioned by everyone around her even though the teenager herself is under the impression that her reality makes perfect sense is probably not easy. Yet Sarah Moon’s undeniable wizardry is evident in her sensitive storytelling. Sparrow can be challenging even for an experienced author  to create as it is a potential minefield if not handled well. It can fall apart easily. After Nathan Filer’s The Shock of Fall this is another great young adult novel to add to a school reading list. Perhaps to be read in conjunction with Matt Haig’s Reasons to Stay Alive which is not a young adult novel, nevertheless an excellent memoir about coming-to-terms with depression and easily accessible to readers of all ages.

to create as it is a potential minefield if not handled well. It can fall apart easily. After Nathan Filer’s The Shock of Fall this is another great young adult novel to add to a school reading list. Perhaps to be read in conjunction with Matt Haig’s Reasons to Stay Alive which is not a young adult novel, nevertheless an excellent memoir about coming-to-terms with depression and easily accessible to readers of all ages.