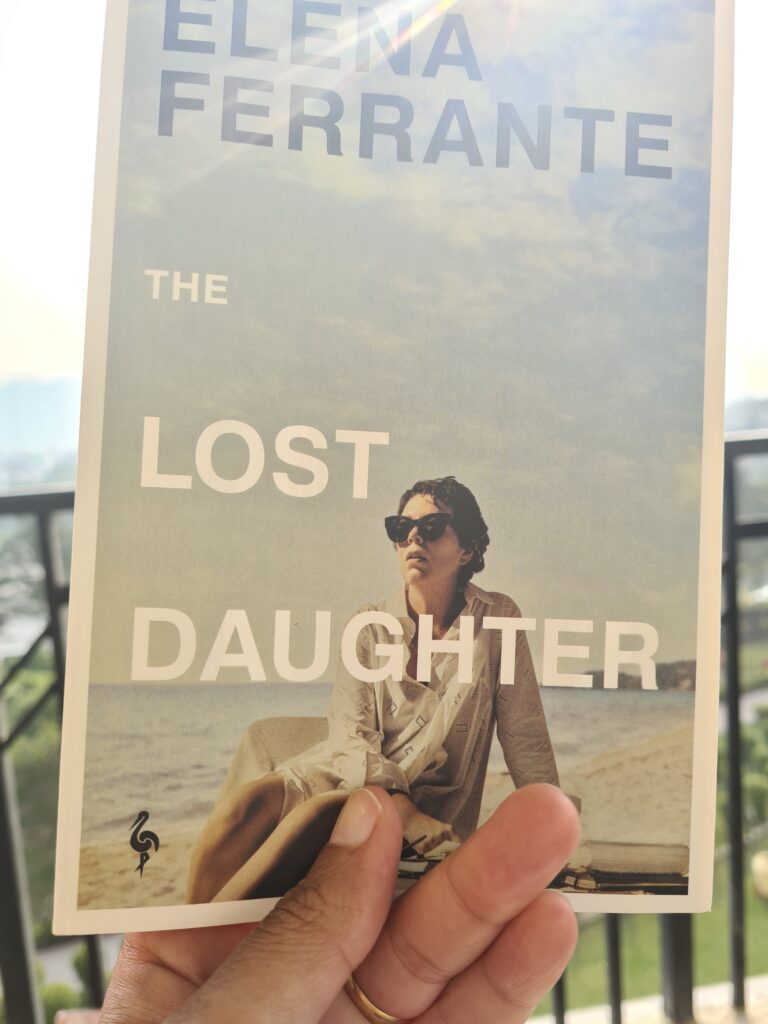

“The Lost Daughter” by Elena Ferrante

The Lost Daughter by Italian writer Elena Ferrante is about forty-eight-year-old Leda, an English Literature teacher, who is on holiday in southern Italy. ( It has been translated by Ann Goldstein and published by Europa Editions.) While at the beach, she meets a Neopolitan family that eerily reminds her of her own childhood. Large group, multi-generational, raucous, talking nonstop, and unforgettable. They exist. They manage to be noticed. A couple of the women, Nina and Rosaria, befriend Leda. The novella revolves around the disappearance of Nina’s daughter Elena’s doll and the unusually large proportions it assumes in the story — for propelling the plot forward and the significance it assumes for Leda. The doll vanishes at the same time as Elena had also disappeared from the beach and a manhunt had been organised for her. Fortunately, Leda spotted the child crying by herself, in the midst of a crowd where no one seemed to be perturbed by the little girl’s anxiety. She returns the little girl to her relieved mother.

The Lost Daughter as a title is a true reflection of the story’s contents. At the same time, it becomes a metaphor at multiple levels for the daughters that Leda left with their father, her complicated relationship with her own mother, the doll that Elena would look after as if she were her own child, and of course as a figure of speech for the many, many women who are left stranded, lonely, without anyone caring for them and scrubbing the women of all identity — making them just one more nameless person in a crowd, part of one’s background.

What had I done that was so terrible, in the end. Years earlier, I had been a girl who felt lost, this was true. All the hopes of youth seemed to have been destroyed, I seemed to be falling backward towards my mother, my grandmother, the chain of mute or angry women I came from. Missed opportunities….I was frustrated.

….

This is particularly true for many women when they enter motherhood and are expected to be the good, fulfilling mother from the moment the “creature” inside them begins to develop. It is a “shattering” experience that leaves the women in “turmoil”. It is an exhausting process that leaves the mother/individual little time for herself as she has to fend for the babies.

I hadn’t been able to open a book for months; I was exhausted and angry; there was never enough money, I barely slept.

…

Physical tiredness is a magnifying glass….Love requires energy, I had none left.

The incidents in the story become a trigger for Leda to reflect upon her past, her relationships especially those with her daughters and years later, trying to fathom why she left them at the ages of four and six years old. She abandoned Bianca and Marta and had nothing to do with them for three years. She had been persuaded by her professor to attend an international conference in London on E.M.Forster. There, amongst her peers, she realised she was being recognised as an upcoming young scholar whose works were already being cited by other specialists.

I was overwhelmed by myself. I, I, I: I am this, I can do this, I must do this.

Sometimes you have to escape in order not to die.

…

Reading, writing have always been my way of soothing myself.

…

“I loved them too much and it seemed to me that love for them would keep me from becoming myself.”…

“And how did you feel without them?”

“Good. It was as if my whole life had crumbled, and the pieces were falling freely in all directions with a sense of contentment.”

“You didn’t feel sad?”

“No, I was too taken up by own life. But I had a weight right here, as if I had a stomachache. And my heart skipped a beat whenever I heard a child call Mama.”

…

Then Leda returned to her family for a few years.

..I realized that I wasn’t capable of creating anything of my own that could truly equal them.

…

“So you returned for love of your daughters.”

“No, I returned for the same reason I left: for love of myself.”

At the moment, this book, has got a new lease of life as it has been adapted to the screen and is available on Netflix. It has Oscar-winner Olivia Coleman playing the lead role. The film is actress Maggie Gyllenhal’s debut as a film director and she has already won awards for it. The film adaptation is true to the book in representing many of the incidents, otherwise it takes many liberties. For instance, the family on the beach in the film are not Neopolitan as is stressed in the book and is the fundamental reason for triggering many memories for Leda. Even Olivia Coleman comes across as a much older woman than the forty-eight-year-old character in the book. The maturity levels of the two women — the character in the book and that played on screen — impact the storytelling. But there is no doubt that the film is a brilliant artistic interpretation by very strong, thinking, women professionals on how these characters need to be played. No more. Reading the book and watching the film are two very independent acts and witnessing of two very distinct creative performances, two works of art.

Many of the reviews of the film are applauding it and very rightly so. But by not including the book in their articles, critics are doing a disservice to the book and to women’s literature. It is stories like The Lost Daughter that make the ideas and principles of various women’s movements accessible to the ordinary reader. Leda is a possible role model by articulating clearly the reasons for her choices. The complexity of these decisions is evident in the last few lines of the story when Leda’s daughters, now based in Toronto with their father, call their mother, shouting gaily into her ear:

“Mama, what are you doing, why haven’t you called? Won’t you at least let us know if you’re alive or dead?”

Deeply moved, I murmured:

“I’m dead, but I’m fine.”

Read The Lost Daughter.

6 Feb 2022