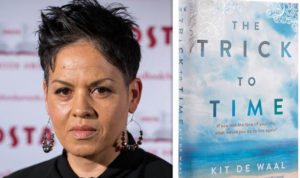

Kit de Waal’s “The Trick to Time”

‘One day,’ he says, and his voice is kind so Mona knows she isn’t getting a telling-off, ‘one day, you will want these hours back, my girl. You will wonder how you lost them and you will want to get them back. There’s a trick to time.’

‘One day,’ he says, and his voice is kind so Mona knows she isn’t getting a telling-off, ‘one day, you will want these hours back, my girl. You will wonder how you lost them and you will want to get them back. There’s a trick to time.’

‘What’s the trick, Dadda?’

He likes to explain things so Mona expects a good long answer that might delay them getting back home.

‘You can make it expand or you can make it contract. Make it shorter or make it longer,’ he says.

Kit de Waal’s second novel The Trick to Time is about a young Irish girl Desdemona usually called Mona who leaves Ireland to work in Birmingham. It is the 1970s. On her first night in the city she meets William, an Irish lad, and soon after a whirlwind romance they are married. She is not even twenty. Mona had left her father and the tiny Irish village she grew up in to get a job. While in Birmingham she enrolled herself in evening classes to be a seamstress. William and she are extraordinarily happy with each other till a terrible tragedy shatters their world. It is compounded by the fact that William is caught in the ghastly IRA bombings that happened in Birmingham on 21 November 1974.

When the novel opens Mona, now nearly sixty, is an established doll-maker, mostly heirloom pieces, an exquisite seamstress of dolls clothes and sells beautiful wooden dolls, some fitted out in vintage wear. Dresses she painstakingly puts together by scouring thrift shops and flea markets for fabric and pieces of clothing which if need be she carefully pulls apart to recreate the clothes for her dolls. She relies upon a carpenter to make her wooden dolls. Ever so often her door will ring and a lone woman will walk in with the words “Gayle sent me.” A very peaceful air envelops the two women, strangers, while they converse engulfing the “howling grief” of the customer but Mona with immense tenderness seeks the relevant information about weight and fixes the next appointment. It all happens civilly without adding to the trauma of the grieving mother.

The Trick to Time is an extraordinary novel suffused with extreme tenderness, gentleness, understanding and kindness even though there is pain and misery. Its focus is on living life joyfully, considering each moment as blessed, without ignoring or forgetting that which hurts, is what comes through beautifully particularly in the poised manner in which Mona conducts herself. While being an efficient seamstress who sells exquisite dolls, she quietly helps keening mothers deal with the loss of their newborns, sometimes many years after the birth of the stillborn. Her healing sessions are unusual. She requests the carpenter to carve and polish a block of wood equal in weight to that of the grieving mother’s lost newborn. Then tucking the woman into a comfortable chair holding the piece of wood draped in a garment belonging to the beloved child, Mona weaves a magnificently hypnotic tale involving shared moments between mother and child through adulthood. The pained grief the reader feels too in these private moments are movingly created by the writer and yet there is an abundance of kindness and sympathy present.

The Trick to Time is definitely literary fiction that is recognizably working class in its themes, language, characters and stories. For instance it is not only a history of the changes in maternal care and attitude towards stillborn from the gruesomely cold attitude of the 1970s nurses to a more caring and understanding attitude including of setting up support groups for mothers in today’s day and age. The novel is a sensitive study of not only how women are affected but also men as evident in William’s reaction to the loss of his daughter. Kit de Waal also talks about the working class thereby subverting that which is even today considered acceptable in contemporary literary fiction — this at a time when the conversations about inclusive or diversity in publishing are increasing rapidly. In a fabulous talk “Where are all the working class writers?” on BBC 4 Radio broadcast on 23 Nov 2017 she said “The more we reinforce the stereotypes of who writes and who reads, the more the notion of exclusivity is reinforced. It takes balls to gatecrash a party.” She reiterates talking about class is still an awkward conversation to have. In an interview with Boundless she was asked about Lionel Shriver’s ( now infamous remark) about “cultural appropriation” and if a writer should only write from their point of view; to which Kit de Waal said she concurred with Lionel Shriver but added wisely: “I have written to some extent about certain experiences I have had or have been close to. I would certainly write about experiences I haven’t had – I probably will do in future novels – provided I was certain of three things – and this is especially true where the experience was a sensitive subject (as is race, racism, adoption, mental health and stillbirth, as in my first two novels) a) that I was going to say something new or different to what had already been said on the subject, b) that I had done as much research as I possibly could including talking to people who had had the experience or were from the community, reading, watching films and so forth until I was immersed in that experience, certain of my facts, had paid the subject sufficient attention and had taken no shortcuts, c) that if someone criticised me for writing about that subject or experience I would be able to take that criticism.All of this is a question of respect. Lionel Shriver is completely right that we can write about whatever we want. Whether or not we are entitled to write whatever we want is an entirely different matter. Entitlement is a dangerous attitude, bringing with it notions of privilege, possession and exclusion. We only own our story and then only from our point of view – which one of us agrees with our siblings about every detail of our childhood? Stray from our narrow experience and we trespass on someone else’s, potentially. Yes, write whatever you want but interrogate yourself as to what you bring that is different, that is new, that is unique and whether or not you are best placed to be the one to tell that story. And always guard against arrogance and disrespect.”

Although Kit de Waal reiterates in an essay in the Guardian “…without talking about the upper- or middle-class white men and women who wrote the classics and some of the masterpieces of literature. I love their writing, respect – no, envy – their skill and craft, and cherish those books that tell us so much about the world and what it is to be human. These are works that, as Italo Calvino says, haven’t finished saying what they have to say. This isn’t a plea to take them off the shelf. It isn’t a case of us or them; it’s a case of us and them. Shove all those other books up a bit and make room on the shelf for stories from all of the communities that make up the working class. We do literature and ourselves a disservice if we don’t.” ( “Kit de Waal: ‘Make room for working class writers’ ” 10 Feb 2018, The Guardian). In fact she crowdfunded Common People: An Anthology of Working Class Writers — a collection of essays, poems and pieces of personal memoir, bringing together sixteen well-known writers from working class backgrounds.

Kit de Waal has this incredible talent of making visible particularly that of female experience which is usually not  seen in mainstream literary fiction especially when it comes to working class fiction. She is the 21C version of Charles Dickens. With her memorable and absolutely stupendous debut novel My Name is Leon she focused upon growing up as a child in early 1980s in a working class neighbourhood and related issues of fostering, childcare, angry children and looking out for one another. Kit de Waal has worked in family and criminal law for many years, has been a magistrate and written training manuals on fostering and adoption; she also grew up with a mother who fostered children. In The Trick to Time she makes visible tiny but crucial details such as Mona looking after the carpenter, her kindness extending itself to warmly embrace the grieving mothers without letting on that she herself would like to keen for her stillborn child, or simply the descriptions of her living alone at home peacefully and pottering. These tiny actions are liberating as most often than not women’s actions are either dictated or circumscribed by a man in their lives, who loves to colonise their time. This is evident in how the German Karl tries to woo Mona largely by disrupting her peaceful schedule. All these details that would otherwise be considered too pedantic for literary fiction are in an ever so gentle manner brought into focus.

seen in mainstream literary fiction especially when it comes to working class fiction. She is the 21C version of Charles Dickens. With her memorable and absolutely stupendous debut novel My Name is Leon she focused upon growing up as a child in early 1980s in a working class neighbourhood and related issues of fostering, childcare, angry children and looking out for one another. Kit de Waal has worked in family and criminal law for many years, has been a magistrate and written training manuals on fostering and adoption; she also grew up with a mother who fostered children. In The Trick to Time she makes visible tiny but crucial details such as Mona looking after the carpenter, her kindness extending itself to warmly embrace the grieving mothers without letting on that she herself would like to keen for her stillborn child, or simply the descriptions of her living alone at home peacefully and pottering. These tiny actions are liberating as most often than not women’s actions are either dictated or circumscribed by a man in their lives, who loves to colonise their time. This is evident in how the German Karl tries to woo Mona largely by disrupting her peaceful schedule. All these details that would otherwise be considered too pedantic for literary fiction are in an ever so gentle manner brought into focus.

With the generous publishing advance the author received for her first novel she set up the Kit de Waal Creative Writing Fellowship to help improve working-class representation in the arts. Launched in October 2016 at Birkbeck’s Department of English and Humanities, the scholarship provides a fully funded place for one student to study on the Birkbeck Creative Writing MA, and also includes a generous travel bursary to allow the student to travel into London for classes and Waterstones’ vouchers to allow the student to buy books on the reading list. The inaugural scholarship was awarded to former Birmingham poet laureate Stephen Morrison-Burke.

The Trick to Time was on the longlist of the Women’s Prize 2018 and it is a pity it never made it to the shortlist. Nevertheless it is a book meant to be read and shared. It will be a sleeper hit for it is bound to be read by book clubs worldwide as well has great potential of being adapted for cable television or cinemas. The Trick to Time is a book that will endear itself to many as it justifiably should!

Read it.

Kit de Waal The Trick To Time Viking, an imprint of Penguin Books, London, UK, 2018. Pb. pp.260

27 April 2018