( I spotted the following post on Prof. Aloke Kumar‘s Facebook wall regarding an ongoing exhibition in Calcutta. With his permission I have reposted it here with additional images from his own collection.)

( I spotted the following post on Prof. Aloke Kumar‘s Facebook wall regarding an ongoing exhibition in Calcutta. With his permission I have reposted it here with additional images from his own collection.)

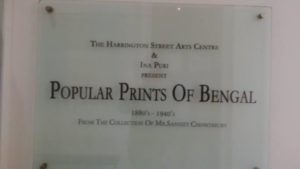

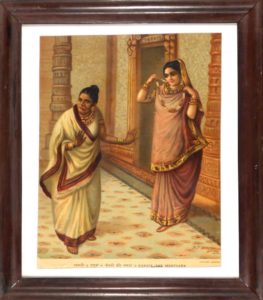

An exhibition of lithographs and oleographs from 19th and 20th  Century Bengal presented by Ina Puri from the collection of Sanjeet Chowdhury has been mounted at the Harrington Street Arts Centre.

Century Bengal presented by Ina Puri from the collection of Sanjeet Chowdhury has been mounted at the Harrington Street Arts Centre.

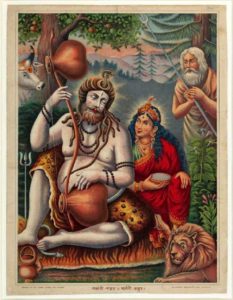

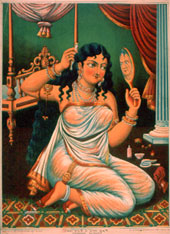

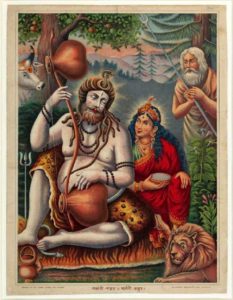

Such exhibitions are mounted to showcase a particular school of Paintings or Prints, to take pride in a collection created over years, to sell the artworks and to make it available to general public for appreciation and educative value. In my youth I saw these prints usually garish and stylised pictures of gods and goddesses and mythological scenes. They were sitting, framed, among the deities of Grandma’s puja alcove. Or lending period flavour to some battered publication as a quaint colour plate.

Such exhibitions are mounted to showcase a particular school of Paintings or Prints, to take pride in a collection created over years, to sell the artworks and to make it available to general public for appreciation and educative value. In my youth I saw these prints usually garish and stylised pictures of gods and goddesses and mythological scenes. They were sitting, framed, among the deities of Grandma’s puja alcove. Or lending period flavour to some battered publication as a quaint colour plate.

However on visiting the well curated exhibition at such a well-appointed unique gallery I was taken aback by the thin  visitors in the exhibition. What a waste! There is still time. The exhibition is opened till 14th February. There is a Sunday in between.

visitors in the exhibition. What a waste! There is still time. The exhibition is opened till 14th February. There is a Sunday in between.  Do rush to the Centre. You will never get an opportunity to witness such a collection. Since I possess a collection similar to this one, I am telling you ,do make a pilgrimage.

Do rush to the Centre. You will never get an opportunity to witness such a collection. Since I possess a collection similar to this one, I am telling you ,do make a pilgrimage.

I appreciate and enjoyed it so much for the aesthetic qualities of the exhibits as for the manner in which it has been presented, themed and placed in the right context the form that once could be seen in households slowly disappearing.

Since these prints have of late become collectibles worthy of being exhibited, they have acquired an altogether  different status that would not be wrong to describe as exalted. Ina Puri, art provocateur, treats them with the seriousness due to them in her authoritative introductory note which hangs on the wall.

different status that would not be wrong to describe as exalted. Ina Puri, art provocateur, treats them with the seriousness due to them in her authoritative introductory note which hangs on the wall.

She divides the prints into three distinct categories, depending on their  provenance: prints from Chorbagan, Art Studio and from other Bengal presses. Fortunately for the visitor, the names of the artist, publishing house, and place where printed are stated on each print. At the tailend, there could have been a wall sign on the techniques of lithography, chromolithography and oleography, which will help viewers appreciate the exhibition better.

provenance: prints from Chorbagan, Art Studio and from other Bengal presses. Fortunately for the visitor, the names of the artist, publishing house, and place where printed are stated on each print. At the tailend, there could have been a wall sign on the techniques of lithography, chromolithography and oleography, which will help viewers appreciate the exhibition better.

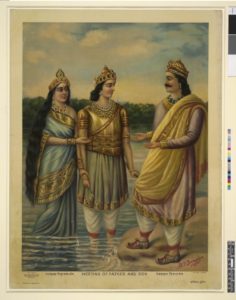

The history of these prints began in Calcutta around 1878, when a chromolithography press opened on Bowbazar Street, followed by Kansaripara Art Studio and Chorebagan Art Studio. What will interest the informed are prints by identified though less-known artists such as Bamapada Banerjee and Shital Bandopadhyay from Calcutta. The artists who created these were often trained in Western academism, yet the gods and goddesses churned out by the presses inhabited a mythical world beyond the bounds of realism. Many such prints were closely linked to the freedom struggle, depicting nationalist leaders like Bankim Chatterjee, as well as Surendra Nath Banerjee.

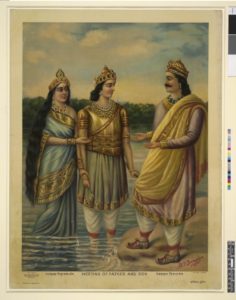

The history of these prints began in Calcutta around 1878, when a chromolithography press opened on Bowbazar Street, followed by Kansaripara Art Studio and Chorebagan Art Studio. What will interest the informed are prints by identified though less-known artists such as Bamapada Banerjee and Shital Bandopadhyay from Calcutta. The artists who created these were often trained in Western academism, yet the gods and goddesses churned out by the presses inhabited a mythical world beyond the bounds of realism. Many such prints were closely linked to the freedom struggle, depicting nationalist leaders like Bankim Chatterjee, as well as Surendra Nath Banerjee.

These prints were responsible for the decline of Kalighat painting and also in large part to its inability to continue to  adapt and compete with incoming forms of cheap prints. In the early 20th century, German oleographic printing techniques reached India and printmakers were swiftly able to out produce Kalighat painters. Calcuttans

adapt and compete with incoming forms of cheap prints. In the early 20th century, German oleographic printing techniques reached India and printmakers were swiftly able to out produce Kalighat painters. Calcuttans

Ganga Presenting her son Devavrata Future Bhisma to his Father Santanu Lithograph Print by B.P-Banerjee 1923were seduced by the photorealistic quality of print images, another value instilled by the influx of European art. By the 1930s, there were few if any patuas were still near the Kalighat temple. The majority sought work elsewhere or returned to the villages from whence they had come.

were seduced by the photorealistic quality of print images, another value instilled by the influx of European art. By the 1930s, there were few if any patuas were still near the Kalighat temple. The majority sought work elsewhere or returned to the villages from whence they had come.

In the next phase those who felt the fear of losing Indian culture to British influence and rule would soon use these prints as a tool for elite nationalistic self-determination, setting in motion the culture of patronage that would both support and take forward this popular print art into the 21st century. The potential that lay in harnessing popular mythological images for a nationalist cause. They saw, in these pictures, the portrayal of a glorious past, the propagation of which would induce in the  beholders a sense of belonging to a great and once glorious tradition. India began to be projected as a country that had, over the centuries, been oppressed by foreign powers which had eroded and manipulated her traditional values; her culture was portrayed as one which, though failing in material advancement, had an inherent metaphysical strength and which enabled her to absorb past and present invaders. This was a rallying call to muster popular support for an independent India, the India for which gods and national heroes had struggled from time immemorial.

beholders a sense of belonging to a great and once glorious tradition. India began to be projected as a country that had, over the centuries, been oppressed by foreign powers which had eroded and manipulated her traditional values; her culture was portrayed as one which, though failing in material advancement, had an inherent metaphysical strength and which enabled her to absorb past and present invaders. This was a rallying call to muster popular support for an independent India, the India for which gods and national heroes had struggled from time immemorial.

When Europeans came to India, the indigenous printmaking industry primarily comprised block printing on textiles. With the introduction of new modes of printing, including etching, lithography, oleography, intaglio and linocut. Indian artists were trained in the  medium by the colonisers. It was introduced in the Government College of Art and Craft too. But back then, printmaking was encouraged to build the workforce and for technicians needed to sustain the print industry, not as a fine art.

medium by the colonisers. It was introduced in the Government College of Art and Craft too. But back then, printmaking was encouraged to build the workforce and for technicians needed to sustain the print industry, not as a fine art.

The exhibition depicts a rich heritage replete with heroic legends from ancient epics, which were deeply ingrained in many layers of the Bengali psyche. The sheer reverence and admiration for these legends could be readily manipulated into fervent passion. The transformation of this passion into uniform images that could be easily replicated and widely distributed became one of the most potent

weapons in the hands of those leading the nationalist movement. In these pictures, the gods were equipped with nationalistic paraphernalia and national leaders were projected almost like celestial beings.

Prints distributed during the last phase of the struggle for independence were printed using the half-tone technique. New developments in printing technology also resulted in a change of aesthetics. The size of the prints tended to be smaller than that of the oleographs. New techniques dispensed with the highly glossy quality of the earlier prints. Now printed in only three colours — a far smaller palette as compared to the fourteen or seven colours of the oleographics prints — they had a somewhat drab appearance, rather like newsprint. Since many of these prints were made in small workshops, the artists worked them like collages of newspaper picture clippings, introducing a fair amount of their own folksy iconography

At the end of the 19th Century, a printing industry devoted to the production of pictures of deities and mythological themes was established. Being mass produced, they were the most visually influential medium of visual communication of the then socially and culturally fragmented Indian society, subsequently becoming a vehicle for political propaganda as well.

The show unfolds a fascinating narrative in terms of iconography and ideas, techniques and styles. There are a few realistic portraits in monochrome from the late 19th century that reveal sound training and are printed by Calcutta Art Studio. Art is preserved so to say, by other presses, too. Like Chorebagan Art Studio, Kansaripara Art Studio and Imperial Art Cottage which seem to have catered to different taste, both religious and pop.

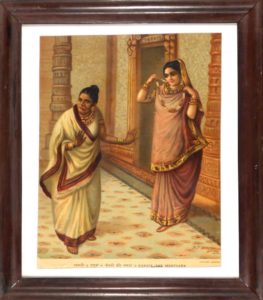

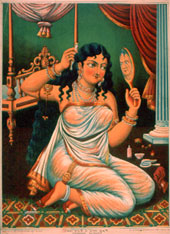

So while Radha and Krishna in shimmering clothes with improbably lavish folds are placed in landscapes that quote miniature stylisation, the curvaceous Pramada Sundari in a diaphanous sari preening herself before a hand-held mirror ‘ a gesture enshrined in the lexicon of the Indian arts through sculpture, painting and dance-brings to mind Kalighat pat. Though perspective isn’t quite mastered, an appetite for elements of Western art seems evident.

___________

Images : Images are from the Exhibition titled : Popular prints of Bengal being held at Harrington Art Centre.

Those individual and unframed for reference and for a closer perspective are from the collection of Prof. Aloke Kumar

12 February 2017

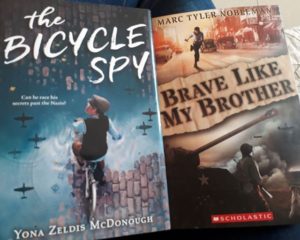

Of late there has been an increase in the amount of historical fiction set during the second world war by contemporary writers. These are two wonderful examples. The Bicycle Spy introduces young readers to the Resistance and German occupation of France. It is a story told from the perspective of a young boy who discovers his classmate is a Jew from Paris and needs protection. With the help of his parents he sets out on his mission. Likewise Brave Like My Brother is about a young American soldier who is recruited and within three days packed off to England and later, France. The story is told via letters he exchanges with his younger brother. As the writer says he did take some creative license to tell it but it’s embedded in facts such as Eisenhower’s visit to the Allied troops in Europe and the use of inflatable armoured vehicles to be used as decoy before D-day.

Of late there has been an increase in the amount of historical fiction set during the second world war by contemporary writers. These are two wonderful examples. The Bicycle Spy introduces young readers to the Resistance and German occupation of France. It is a story told from the perspective of a young boy who discovers his classmate is a Jew from Paris and needs protection. With the help of his parents he sets out on his mission. Likewise Brave Like My Brother is about a young American soldier who is recruited and within three days packed off to England and later, France. The story is told via letters he exchanges with his younger brother. As the writer says he did take some creative license to tell it but it’s embedded in facts such as Eisenhower’s visit to the Allied troops in Europe and the use of inflatable armoured vehicles to be used as decoy before D-day.