Indo-French Collaboration: Paris Livre 2020 and New Delhi World Book Fair 2022

On the morning of 11 November 2019, Christine Cornet, Attachée Débat d’Idées et Livre, Institut français India/Embassy of France, invited a few of us Indian publishing professionals to address the visiting delegation. The aim was to give the French visitors a bird’s eye-view of the Indian book market with specific aspects highlighted such as regional language publishing, literary prizes, and literature festivals.

I had been invited to address the gathering on the publishing market of India. I chose to dwell on the characteristics of the publishing market in India along with some important points to consider from the point of view of the French publishers.

In March 2020, India will be the “Guest of Honour” at the Paris Book Fair and in January 2022 France will be the “Guest of Honour” at the New Delhi World Book Fair. This reciprocal invitation for this collaboration was announced during the official visit of President E. Macron in India in March 2018 when he met Prime Minister N. Modi. As a run up to this event, the French Book Office invited a delegation of journalists and cultural experts to visit India and meet publishing professionals. As a run up to this event, the French Book Office invited a delegation of journalists and cultural experts to visit India and meet publishing professionals. The delegation consisted of journalists and cultural experts: Eve Charrin (Marianne and Books), Gladys Marivat (LiRE magazine), Lorraine Rossignol (Télérama), Sophie Landrin (Le Monde correspondent for India and South Asia — Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Maldives), Catherine Fruchon (Radio France Internationale and editor-in-chief/ host of the show Littérature Sans Frontières ), Christian Longchamp ( Artistic advisor and playwright, and co-programmer of the annual multidisciplinary festival ARSMONDO, Opéra national du Rhin, Strasbourg), Sébastien Fresneau ( VP Book and Entertainment Events at Reed Exhibitions France and General Manager of Livre Paris, the Paris Book Fair) and Néguine Mohsseni ( Press Attachée, Institut Français, Paris).

Here are some of the salient points of the roundtable.

Indian Book Market

India is geographically deemed as a sub-continent. It is large. Politically it is a federal structure with a centre and state governments. The population is over 1.3 billion people. 22 languages are recognised officially by the Constitution of India and English is not one of them; instead it is the lingua franca. Interestingly language spoken changes ever so slightly every 20 kms, making it impossible to consider India as a homogenous book market as there are so many languages and scripts to consider.

The Indian publishing industry consists of multiple players. There are publishing agencies like the National Book Trust and the Sahitya Akademi (the organisation for literature) that were established by the government, soon after Independence in 1947. Apart from these the well-known multi-national players exists and a number of independent publishers. Of late the self-publishing market is a growing segment that has resulted in a lot of people getting their works published and new vendors are being established.

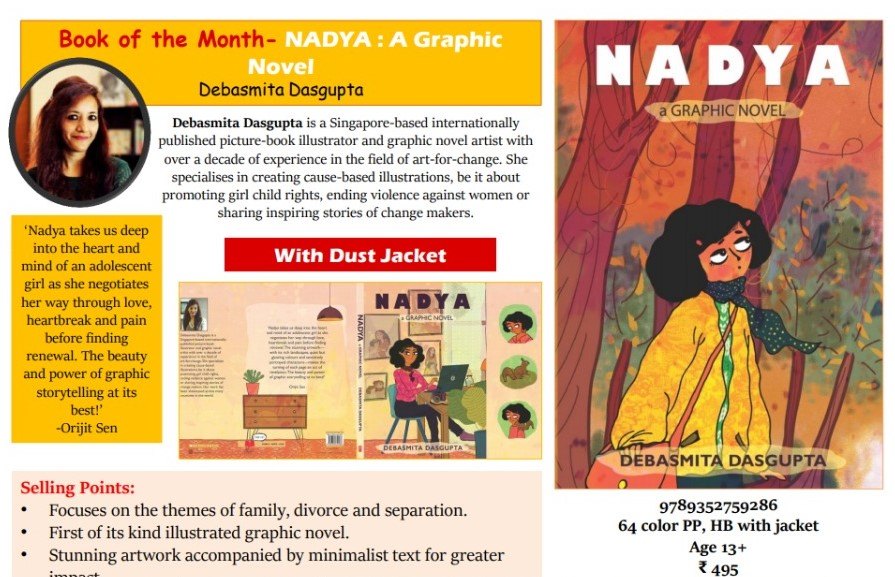

Bookselling happens through brick-and-mortar stores as well as online such as Amazon and Flipkart. Online retail allows many customers/readers to access books from Tier 2 and 3 towns which was not possible earlier. According to Nielsen BookScan, the estimated value of the Indian book industry is approximately US$6.3 billion. It has been more or less at this position since the last Nielsen report of 2015. This is for various factors, most immediate being – GST (July 2016) and demonetisation (Nov 2017). Despite this the book market in India is undoubtedly growing and there is a book hunger. Again this is for multiple reasons, some of them being that more than 60% of the Indian population is under 35 years age, making it young, mostly literate[1] or still studying, so in need of text/books. The K-12 segment constitutes the largest segment of the Indian book market as 50% of the population is below the age of 25 years old. The next segment of interest would be the trade list that consists of MBS (Mind, Body, Spirit) children’s literature, women writing, literary fiction, general fiction (mythology, historical fiction, fantasy, romance, commercial fiction etc.) narrative nonfiction (history, biographies, commentaries, memoirs etc.), cookery books etc. The children’s literature market cannot be ignored for in the past decade it has grown phenomenally. This is not just for the school textbook market but for leisure reading. Some of the factors contributing to its growth have been the presence of school book fairs, literary weeks in schools and writing retreats for budding authors, initiatives started by Scholastic India and now adopted by many other players. Also the insistence of many schools to include supplementary readers and/or books for leisure reading alongside the prescribed curriculum. Also, ten years ago, one of the most popular book festivals for children called Bookaroo was established. Since then it has spread not only to other parts of the country but overseas too. The reading public in this country is growing and this is obvious by the rapid rise of piracy with many of the print editions available at vendors holding large piles of poorly published editions to sell at crossroads and temporary stalls seen on pavements.

Book fairs are very popular too. Unlike some of the international book fairs where the focus is also selling of rights, most fairs in India function as retail outlets. A book fair becomes an occasion for customers to throng the stalls buying their supply of books. The customer profile could vary from individuals, families to institutions browsing looking for titles amongst the front and backlists and often scrummaging through at the remaindered/second-hand bookstalls too. The biggest of these is the New Delhi World Book Fair but then there are many regional book fairs organised too.

A major contributing factor to the book hunger in this country has been the extraordinary growth in popularity of literature festivals beginning with the mother of them all – “Jaipur Literature Festival”. It is organised over a period of five days in January and has many parallel sessions with domestic and international speakers. This model has been emulated across the country with versions of it springing up. Apparently more than 80% of the half million visitors that visit JLF are below the age of 29 years old. This demographic seems to be more or less consistent for other litfests in the country with more and more of the young visible in the audience.

Advancements in digital technology have enabled readers/writers to access books from overseas, participate in online discussion groups, access literature on their phones/pen drives/ebook readers etc. And those that like reading the ebook, then purchase the print copy too. Increasingly it is happening in many scripts.

An indication of the robustness of the publishing are also the increasing number of business conclaves. Four of the prominent ones are the CEOSpeak Over Chairman’s Breakfast organised jointly by the National Book Trust and FICCI (Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce), PubliCon organised by FICCI, Jaipur Book Mark organised by Jaipur Literature Festival and Jumpstart organised by the German Book Office.

Apart from this there are many literary prizes, including specific ones focused on children’s writing, women’s writing, fiction, debut authors, translations etc that have been launched. Some are very lucrative, even awarding the translator, handsomely.

All said and done, the Indian book market is really many markets within a market!

French Book Market

The French book market is smaller but equally robust. Some of the key characteristics are its Fixed Book Pricing, its protection of the brick-and-mortar stores from online players like Amazon and the prominent book fairs like Paris Book Fair. Also publishing translations of World Literature into French.

Indo-French collaboration

The French Book Office’s presence in India has helped foster Indo-French collaborations in the book industry. From sponsoring visits of Indian publishing professionals to France for specific book-related events and vice versa to actively promotes translations and publications of French authors into Indian regional languages under the aegis of the Tagore Publication Assistance Programme (PAP Tagore). French books translated in 2018: 75 titles including 1/3 supported by the Embassy of France. In addition to this the French Institute recently established the Romain Rolland Prize that translates French literature into a regional language. Apart from this consistent soft diplomatic initiative with the active cross-pollination of literature and cultures, the Institut Francais in New Delhi, now facilitated the crossed invitation from the governments of France and India regarding the book fairs. India is the guest of honour at Paris Book Fair 2020 and France will be at the New Delhi World Book Fair in 2022.

A great literary feast awaits the literary communities in

both nations!

[1] According to the Census of India, the definition of “literate” in India is that person who can sign their name.

17 December 2019