My interview with Shikhandin was published in Scroll on Sunday, 10 September 2017 as “‘The writer in me doesn’t have a gender, or is made up of all the genders’: Shikhandin“.

Immoderate Men by Shikhandin is a remarkable collection of stories published by Speaking Tiger Books. These stories meander through the minds of men giving a perspective on daily life which would ordinarily be dismissed. For instance stories like “Room Full of Presents”, “Salted Pinkies”, “Hijras on the Highway” and “Old Man Sitting on a South Kolkata Park Bench, Ruminating” if taken at face-value are regular stories with a mild twist. On the other hand these stories also dissect with finesse the preconceived notion of “What is masculinity?” By delving into the mental makeup of the protagonists the author explores bewildering scenarios; thereby brilliantly subverting notions of patriarchical norms by blurring gender lines as often this confused state of mind is attributed to women and not men.

Here are edited excerpts of an interview with the author:

- How did these stories come about?

Mostly from the world around me, past and present. A couple are from dreams and visions. Some from newspaper articles, photographs, a conversation overheard, a person observed in a crowd, and so on. My stories usually come from life itself, whether dreamt or experienced or watched. “Room Full of Presents” came to me in a pre-dawn dream, all of it, more than a decade ago. I still remember waking from it, the sensations of the dream falling off me like water droplets as I sat up on my bed, trying to stay still, just feeling the story over me, around me. Dreams have their roots in reality, regardless of their form and shape. I was sure I had seen/met the characters somewhere, sometime. “Ahalya” came from a vision of a girl with cascading black hair running up a hill. I was half asleep, but I could see her clearly; the hill felt mysterious; this story crept up on me at first without any specific shape, smoky, yet tangible. Most of my stories run like little movies on a little screen before my eyes – that is my first sighting of the story. I write what I see and hear in that mental screen. This is how it has always been for me, even when I wrote press ads and ad films for a living, years ago.

- How long did it take to write these stories?

The stories in this collection, and others too, were written over a period of almost two decades. I love short stories (and novellas and novelettes), but everybody keeps saying there isn’t a market for them. So for many years I didn’t put together a manuscript of short stories, though I continued to submit and be published in journals, mostly abroad. The earliest story in this collection was written in 2002 and first published in an American Magazine the same year. Individual stories have their own pace. Some, like “Mail for Dadubhai,” was written in one sitting. Ditto for “Ducklings”, “The Vanishing Man” and “Black Prince”. They were edited/fine-tuned after what I call the resting/roosting period. In general, a single story may take me anything from one or two days to a week. I leave them alone after that for as long as it takes, before I revisit. Some may take longer, like “Salted Pinkies”. I was inhabiting the minds of young men, the kind who loiter in Calcutta’s cheap cafes. Even though I was confident of their language and mannerisms, I kept stopping to check, which was difficult because I no longer lived in Calcutta. At times I literally had to mentally transport myself to North Calcutta, walk the streets in my mind. Watching the boys and men all over again. The writing time, I would say, really depends on the story. There is a story that I have left incomplete for almost two decades, because I have imagined several alternative endings for it; one will rise up and push out the others I know. For me, it’s the story that dictates. I am merely the conduit.

- Are they pure figments of imagination or are borrowed heavily from life or inspired by events? (I ask because there is a tone to them that makes me feel as if there is a pinch of reality infused in the stories)

They are both and neither. Like dreams, our imaginings are also based on reality, grounded in the material world. Even a fantasy-scifi movie like Avatar, is at the end of the day, a story about thwarting colonial intrusion. If my stories are relatable, I have succeeded in writing a true one. By true I don’t mean factually correct or historically acceptable. Truth, as I see it, in fiction is about emotional sincerity, that kernel that makes you weep, laugh, sing or rage with or against the character or situation; the narrative that makes you walk through to the end, because it is probable, plausible, relatable, even when the world the story brings forth seems impossible or in the case of literary stories, unfamiliar and totally strange or even shocking. Having said all of the above, yes, there are stories that were inspired by something almost physical. Like “Ducklings” for instance, which is from a photograph I had seen in a newspaper. Avian flu was sweeping across Bengal and Orissa and also Bihar. It was around 2006 I think. There was this black and white photograph of a Bengali woman, weeping as she clutched ducklings, her pets, to her breast. The ducklings were looking innocently back at the camera/photographer. Having grown up with many animals and birds, and experienced the pain of loss, I am not ashamed to say that I wept for that woman, mourned her loss for days. And then I re-imagined her life. “Old Man Sitting on a South Kolkata Park Bench, Ruminating” is inspired from an actual conversation, part of it, that I had heard while passing through a similar park in that city. A few old men were gossiping, about the young girls they had seen or knew, and their daughters-in-law. An incident in the story (kissing a baby boy in the crotch) was actually witnessed by me during my college days in the early eighties, and it is still practised. These traditional Bengali men didn’t/don’t think they were/are doing anything wrong. Saluting a baby boy like that is acceptable; displaying a boy baby is a matter of pride. I stitched that incident into my story. And I became an old man in my head when I wrote it.

- Curiously you chose to write about the world of men while inhabiting their minds. With this technique it is fascinating the multiple layers of reading it lends itself to. How did you train yourself to write in this manner?

For this I really must thank my rigorous advertising training. One of the exercises copywriting entailed was mentally switching places with the consumer. I discovered it works quite well for fiction when you are writing as someone else, seeing things from another’s perspective. My short experience with theatre also helps. That apart, since my childhood, I’ve had this tendency to feel things intensely- be inside the book I am reading or the music I am listening or the movie I am watching, the food I am cooking. Once my mother tore my drawing book into shreds because I hadn’t replied when she’d called me. I wasn’t ignoring her or being disrespectful, I actually hadn’t heard, but of course I wasn’t believed. Similar problems would crop up in school too. Be that as it may, it’s great fun becoming someone or something else even momentarily! Adventure and action, madness and mayhem all in the safety of your own mind. It helps that I am mostly by myself on any week day. I can laugh or cry without being seen as a lunatic! Right now, a part of my head is a dog, doing doggie things; two dogs actually in two totally different stories, so I had to apportion off my grey cells!

- Why use a nom de plume?

Actually in my case, it is not so much as a nom de plume, as acknowledging to myself and everyone, that the writer in me doesn’t have a gender or is made up of all the genders. I ought to have used Shikhandin right at the beginning, but felt shy about it; didn’t want to come across as pretentious. It’s hard enough replying “I write” when folks ask me what I do.

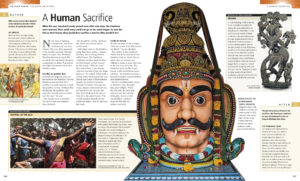

I could have picked up any other gender nonspecific name or initials. There are several versions to the Shikhandin narrative in the Mahabharata. The common thread running through all is that Shikhandin, who was princess Amba of Kashi, in a previous birth, through deep penance and austerities and after several rebirths and a Yaksha’s boon, became a male, Shikhandin, and succeeded in destroying the man (Bhishma) who was responsible for her humiliation and ruin in her first life. Whichever version you read, Shikhandin’s life is a fascinating story of grit, determination and resolve against all odds. For most people Shikhandin represents members of the LGBT community, or those who have rejected gender stereotypes. For me, Shikhandin represents a mind so strong that it can overcome physical boundaries and frailties. It doesn’t matter what you are born as, but who you can become.

I had heard about Shikhandin as a young child listening to tales from the epics. Later, while still in school, I read a bit. Shikhandin has been with me for decades. And because of Shikhandin I questioned male-female roles as dictated by society, and the kind of character and personality ascribed to each as acceptable. I wondered then, and still do, how gender specific are we in the purely intellectual or cerebral sense. How much of our gendered lives are in fact centuries of conditioning. I think it is nonsense that only women can understand women and likewise for men. Physical violence is not a male characteristic, just as daintiness is not a female thing. As a writer, I don’t want to belong to any specific place or slot. I don’t matter, the story does. At the time of writing, I should have the freedom to become whatever is necessary, whatever is required of me, for the story to unfurl as truly as it can.

- When did you gravitate from writing children’s stories to stories for adults?

It’s the other way round actually. I have been writing for adults ever since I can remember. I wish I had started writing children’s stories earlier. That’s another regret, and hope I can make up for lost time now. I was afraid I wouldn’t be good enough. But the Children’s First Contest curated by Duckbill, Parag (an initiative of Tata Trust) and Vidya Sagar School has boosted my confidence . I enjoy reading children’s fiction a lot, even today, after my own children have grown up. And every time I have written a story or poem for children I’ve come away feeling so euphoric – the sheer joy of being a child is like an elixir. I enjoy listening to children’s patter too. Their sense of logic and observation astounds me. They also know more than many grownups about many things.

- Do you think there is any difference in your methodology while writing for children or adults?

Yes, certainly. There is a poem that I’d written and published several years ago, which I think can give you an idea about the kind of heart needed when writing for children:

WHAT THE CHILD DOES

When gossamer tufts come cascading down

From the silk-cotton tree’s bright scarlet crown

Who chases the tufts? Say who does?

The child does

When plump raven clouds thundering their refrain

Suddenly shed weight in vast feathers of rain

Who raises a fountain? Say who does?

The child does

When dew beads strung across blades of new grass

Glisten like rows and rows of glowing elfin glass

Who sees the rainbow? Say who does?

The child does

When within that pupa clinging to a tree

A butterfly softly struggles to be free

Who hears the cry? Say who does?

The child does

When deep down in winter’s icy waters

A timid sun’s shy white ray quivers

Who feels the arrow? Say who does?

The child does

Ah! Everywhere in this world, a new world unfolds

And unwraps and unfurls, expands and grows

Who stands in wonder, then? Say who does?

We do! We do! Yes. But first the child does!

- At times you hold yourself back from describing in greater detail the surroundings or situations. Why?

In short stories less is more – usually, because there are always exceptions to prove the rule! The best are those that without shouting, slip inside your head and start to niggle, urging you, the reader, to create possible endings and solutions, extend the surroundings or simply stay on with the story. I try to emulate that standard. I try.

Shikhandin Immoderate Men: Stories Speaking Tiger, New Delhi, 2017. Pb. pp. 190 Rs 299

12 Sept 2017