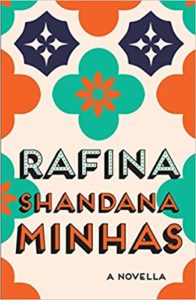

Shandana Minhas’s “Rafina”

Shandana Minhas is a publisher and a writer. She established her independent publishing firm Mongrel Books recently. ( I interviewed her in 2017 for Bookwitty.) Rafina:A Novella published in 2018 but is one of her earliest books. It was written in 2004.

Shandana Minhas is a publisher and a writer. She established her independent publishing firm Mongrel Books recently. ( I interviewed her in 2017 for Bookwitty.) Rafina:A Novella published in 2018 but is one of her earliest books. It was written in 2004.

Rafina is about a young girl who is trying to supplement her newly widowed mother’s income by working in a beauty parlour. Rafina begins to learn the trade from her mother’s best friend Rosie khala who moonlights by attending to rich clients in the comfort of their own home. After a few months, suitably impressed with Rafina’s hard work, Rosie recommends her to the parlour she works in — Radiance. Ever since Rafina could recall she had dreamed of being a model as famous as the one on the hoarding visible outside their cramped government accommodation. Working at Radiance she firmly believed was the first step to earning that fame. Rafina is a lovely modern day version of Cinderella, the beautiful girl who against all odds rose to the top of society to be lauded by the very same people who had earlier ignored her.

Given that it was written in 2004 Rafina is a pleasant enough read with glimpses of the confident writer Shandana Minhas evolves into. I interviewed the author via email. Following are edited excerpts of the interview:

Why a modern day version of Cinderella? Are there not enough versions of the story?

The older, darker versions of Cinderella, hopefully. Nearly every culture has a fable of a woman who uses her beauty as a weapon in class warfare, going back hundreds of years, featuring greed, violence, self mutilation, and lust more nakedly than Disney did. The details vary but the conflict and the endgame –upward mobility through some form of concubinage – remain the same. In the Brothers Grimm’s ‘Aschenputtel’, the dropped shoe is not dropped but stuck in pitch laid down by the king’s son to trap the object of his desire after she keeps running away from his advances. Pigeons fly down to peck out the eyes of the evil stepsisters as they escort the girl they persecuted in and out of the church when she eventually marries him. Rafina is set in a city though. In Karachi the pitch is invisible. And the pigeons would get fried on kundas.

Rafina is an unusual name.

I chose it because I met a Pakistani girl called Rafina when I was young and it was such an unusual name it stayed with me.

Frankly I am super impressed that with your hands more than full with parenting, toddler, ageing parents, new publishing house etc you found the time to see Rafina through publication.

Me too.

Even though you wrote it in 2004 was it your first completed piece of fiction? How is it the novella was not published then, why now?

Rafina was created mid-2004. I was a mother to a toddler, and months away from having a second child; I was in the run up to writing my first novel, Tunnel Vision, a draft of which I completed during that pregnancy. I suspect a lot of young fiction writers feel they can’t really call themselves writers till they’ve had a first novel published, and that at that point in time, facing the idea of being completely subsumed by motherhood, I too was more interested in reaching that – as it turns out entirely illusory – benchmark.

Why Rafina is being published now is because my literary agent, Kanishka Gupta, was looking for a publisher for The Good Citizens, a collection of my shorter fiction; it included Rafina, and there was interest in it as a standalone.

Did you have to tweak it a bit given that it was being published 15 years after it was written?

Apart from minor restructring for flow, and turning up the dial on certain elements (her sexuality, for instance, was subtextual in the first draft) and down on others, I stayed with the story I first told. Teesta Guha Sarkar’s astute editing sharpened Rafina at the level of the sentence and the word by highlighting repetitive words and phrases and expressions that really hadn’t aged well. Kanishka pointed out plot points that needed reinforcing. I also referred to feedback writer friends had offered over the years. I found I was seeing Rafina and the world she was moving through more clearly than I first had. It was an illuminating exercise, draping language onto a fuller-figured story, mouth full of pens instead of pins.

How did this story come about?

The original Rafina was actually about 14,000 words longer than this. When I started writing it I thought it was a short story but it turned out to be a novella. And about six years ago, when The Good Citizens began to crystallise, I tried to condense the novella down to a long short story. And now I’m thinking this is actually the first in a series, a desi Claudine. Rafina continues to refuse to fit into a box just because somebody wants her to.

Tell me more about Rafina. Did she develop as a character as you had wished or is there more to her?

I think she’s well developed for a 17-year-old Pakistani girl, in that there is more to her than the desire to please other people and she embraces that rather than stepping away from it. Setting your own market value rather than letting others set it for you, that’s journey enough for a slim volume, I think.

I like the way you get the crowd of people working furiously in the salon but with distinctive personalities. Are the characters inspired by real people?

For a brief period in my early twenties I had some exposure to the inner workings of the local fashion and beauty industry; the voyeur in me took notes of course. I was always more interested in the people behind the scenes than the ones in the limelight. The ensemble cast of the styling world started as composites of people I came across, or heard about. During fashion or film or TV shoots, my hours with stylists and their assistants were spent haw-ing and hai-ing over their experiences, and gossip about various industry players. Hair-raising. Literally. I’d like to clarify though, in case the owner of the salon my loyalty currently lies with is reading this, that all female employers in the industry are not bad, in fact some treat their employees with the dignity they deserve, and respect their legal rights too. I think we can sense it when we walk into a salon, the happiness quotient of the people who work there. And they often have to do with the littlest things, like putting up a Christmas tree and lights when some of your staff is Christian.

If you had to write this story in 2018 would you change bits and pieces in it? Would you tackle it differently or let it remain?

I’m so glad you asked about tackling it differently or letting it remain as it was. It was THE question, for me. The answer I eventually arrived at was, I could refine language, I could tweak plot, but I couldn’t touch character. Character was what was giving this book the heart people seemed to be responding to, and my cold authorial hands were better left tucked in my armpits.

As for whether I would tackle it differently now, Rafina is in a way a historical document too, as fiction is; it is set in the time right before social media exploded in Pakistan. This is a different world, there is more room for ambitious young women to attempt escape, and more consequences too. I would have no choice but to tackle it differently.

What are you working on next?

I am working on finding the time to write again.

Shandana Minhas Rafina: A Novella Picador India, an imprint of Pan Macmillan Publishing India, New Delhi, 2018. Hb. pp. 170. Rs. 450

17 June 2018