Ashok Shahane and Arun Kolatkar

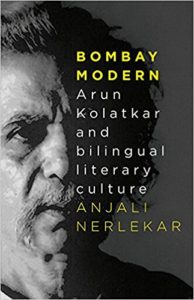

Speaking Tiger Books has recently published the South Asia edition of Anjali Nerlekar’s Bombay Modern: Arun Kolatkar and bilingual literary culture . In the long term it will prove to be a seminal book for its analysis of not only Kolatkar’s contribution to modern Indian literature but also for its context of Indian publishing. Marathi publishing has been a vibrant space for a long time. In fact Bombay Modern discusses at length about the importance of little magazines and their critical influence upon writers by providing a new space for literary writing. Significantly Anjali Narlekar points out:

The writers and editors of little magazines in Marathi and English not only moved in a shared cultural and literary space but were aware of the work done ni the other Indian literatures by the little magazines. One way to examine these interlinks is to look at the network of pathways at the core of regional, national, and international influences.

…

A connection of common influences arcs across the English-Marathi divide between many of these poets. If Mehrotra brought Pound and Ginsberg to bear upon the newly independent Indian society in his English poem, Kolatkar also translated Ginsberg’s “Kaddish” into Marathi for Shahane’s Aso in 1963… .Three prominent examples from the period will illustrate the interconnection across the two worlds. The first is the close literary collaboration between the Beat writers and the Bombay poets. It is a known fact that Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky read their poetry on Alkazi’s terrace in 1962 on their visit to Bombay, but the Beat poets were also interacting with both the English writers and the vernacular writers in Bengal and in Maharashtra, like Ashok Shahane and Kolatkar in Bombay. Shahane published Ginsberg’s poetry in English and in Marathi translation in Aso as well as the work by Orlovsky in its original English. Shahane also wrote a poem in the little magazine Timba where he mocks the rabid fervor generated by religious personalities like the Shankaracharya. Shahane trivializes such religious zeal with a seemingly frivolous comparison and connection with the Beats and with Hollywood:

the world is a dream

the Shankaracharya has said

as Allen reported

Arjun was the last man

and maybe also Burt Lancaster

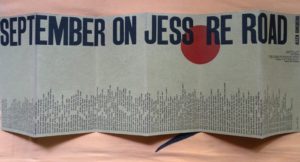

“Allen” here refers to Allen Ginsberg, and in this poem, Shahane self-confidently accepts the long way home when he states that he learned Shankaracharya’s teaching through hearsay from Ginsberg. It shows the defiant refusal to accede to claims of monolingual affiliations. It is also a little-known fact that Ginsberg’s poem “September on Jessore Road” first appeared in Bombay, published by Ashok Shahane. When the Bangladesh War began in 1971 and Ginsberg wrote the poem, Shahane printed and distributed copies of it and gave the proceeds to Bangladesh aid committee set up in Bombay. Followed closely, such circuits of the global invariably lead to the space of the local.

“Allen” here refers to Allen Ginsberg, and in this poem, Shahane self-confidently accepts the long way home when he states that he learned Shankaracharya’s teaching through hearsay from Ginsberg. It shows the defiant refusal to accede to claims of monolingual affiliations. It is also a little-known fact that Ginsberg’s poem “September on Jessore Road” first appeared in Bombay, published by Ashok Shahane. When the Bangladesh War began in 1971 and Ginsberg wrote the poem, Shahane printed and distributed copies of it and gave the proceeds to Bangladesh aid committee set up in Bombay. Followed closely, such circuits of the global invariably lead to the space of the local.

The poets Arun Kolatkar (Left) and Raghu Dandavate (second from Left) and Shahane (third from Left) were part of a group that would meet every Thursday afternoon for its kattas.

The second example is Arun Kolatkaris Jejuri, which includes poems that traverse repeatedly across linguistic lines. The poem “The Priest” from Jejuri appeared in Marathi on pages 88-89 of the 1977 special issue of Rucha on Kolatkar even as a book of poems in English, published by the small Clearing House Press, won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize that year. The history of this book of poems manifests the entangled nature of the multilinguistic sabottari worlds. Initially one of the poems from the Jejuri collection appeared in the English little magazine Dionysus ( edited by Abraham Benjamin and Shirish Pradhan) , which promptly lost the manuscript of the collection of poems. It was then rewritten in English and appeared in full in A.D. Gorwala’s Opinion Literary Quarterly in 1974, then was apparently shown to Arun Khopkar ( who published a poem from it in Rucha in 1977, when the English book of poems was published), adn eventually appeared in a Marathi book of poems posthumously in 2011. Dilip Chitre’s work demonstrates a similar catholicity in its publishing spaces: his translations from the French poets appeared in the Marathi Satyakatha ( December 1963), his translations of the Marathi poet Mardhekar in the English little magazine Poetry India ( 1966), and translations of the Marathi Tukaram in Mehrotra’s English little magazine fakir ( 1968).

A crucial third way in which the little magazines provided a mixed space for writers emerges when one considers the presence of Dalit writers and editors in the sabottari years. The iconoclastic philosophy of the little magazines borrowed its energy from the foundational rage of the Dalit writers in its refusal of tradition in most of its manifestations, be it in vocabulary, imagery, poetic structure, or representative realisms. The little magazine movement was clearly influenced by the Ambedkar revolt in the 1950s and the subsequent Marathi publications of writers like Shankarrao Kharat and Baburao Bagul in the early 1960s when the first Marathi little magazines started appearing at the same time ( Shahda in 1955 and Aso in 1963). the little magazines also provided a space for many rising Dalit writers to showcase their work. There is a synergy between the two movements that is important to note. The sabottari poetry is notable for its emphasis on the material as well as the textual. The angry materialism seen in the poems of Chitre or Kolatkar is comparable in terms of literary technique with much of Dalit literature’s emphasis on the body.

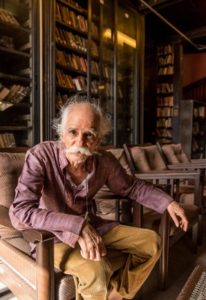

There is much, much more to discover in this fabulous book. Interesingly enough Caravan magazine’s July 2017 issue has published a magnificent profile of Ashok Shahane. It is worth reading for its insight into little magazines the weekly meetings of the Bombay poets and how as Shahane a close friend of Kolatkar was entrusted with the manuscript of Bua. ( “The Man Who Wrote (Almost) Nothing” Ashok Shahane’s deep imprint on Indian modernist literature )

Kolatkar also gave Shahane a warning: “He said to me, you will probably have to wait 30 years — a generation — so that the intolerance outside decreases, before you can publish it. Now 12 years have passed, and the intolerance has increased, not decreased.”

…

” I don’t think society will be able to accept it now,” he said. “Conservatism has increased. And from conservatism has come intolerance, and from that various things. Now, how many years I’ll have to wait I don’t know.”

There is a story Shahane likes to tell about the medieval Marathi saint-poet Dnyaneshwar, regarding the relationship between the word and the world. Dnyaneshwar said that when we look for the sliver of the moon, the branch of a tree becomes useful as a guide to our eyes. Words are that branch, not the sliver of the moon itself.

“What is literature? Literature has nothing to do with the real world. I mean, at the same time it has everything to do with the real world,” he said. “You need readers who can maintain this balance. Literary matters will stay in literature, and the interpretation will stay in your mind. You won’t come out and fight in the street. At least this much I expect. But I don’t think I can expect that. Someone will take offence, and then, things will unravel.”

18 July 2017