Ruskin Bond

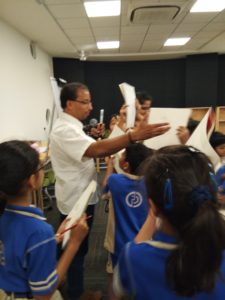

Last year I spotted Ruskin Bond at a literary festival but it was impossible to see him clearly. It was also the first time I saw an author in India encircled by large security men, more like bouncers seen outside clubs. They not only towered over Ruskin Bond but were very well built and were an extraordinary sight to behold. A testimony too the fan following Ruskin Bond has in India. He needed protection from his fans. Children flocked to him in droves. Parents prostrated themselves in front of the literary festival oragnisers to allow their children into the hall even though it was filled to capacity. Astounding indeed when you realise that Ruskin Bond prefers his solitude, tucked away up in his beloved hill town of Mussorie.

Last year I spotted Ruskin Bond at a literary festival but it was impossible to see him clearly. It was also the first time I saw an author in India encircled by large security men, more like bouncers seen outside clubs. They not only towered over Ruskin Bond but were very well built and were an extraordinary sight to behold. A testimony too the fan following Ruskin Bond has in India. He needed protection from his fans. Children flocked to him in droves. Parents prostrated themselves in front of the literary festival oragnisers to allow their children into the hall even though it was filled to capacity. Astounding indeed when you realise that Ruskin Bond prefers his solitude, tucked away up in his beloved hill town of Mussorie.

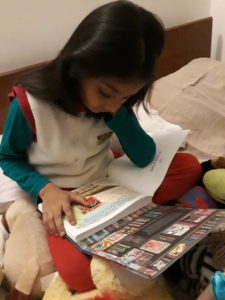

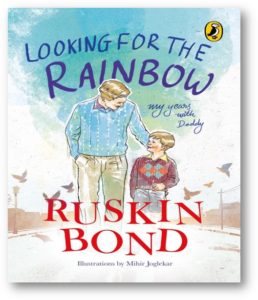

On 19 May 2017, Ruskin Bond turns 83. To celebrate it his publishers  have scheduled a bunch of publications. Puffin India has released Looking for the Rainbow — a memoir he has written for young readers describing the time he spent with his father in Delhi. It was during the second world war. His father was with the Royal Air Force ( RAF), stationed at Delhi. Ruskin Bond’s parents were divorced and his mother was about to get married for the second time. His father decided Ruskin Bond could stay with him for a year in Delhi where he had some rooms rented — at first off Humayun Road and then later nearer to Connaught Place. Ruskin Bond remembers this time spent in Delhi fondly even later when he was sent off to boarding school in Simla. In fact decades later he recalls with a hint of sadness that Mr Priestly, his teacher, did not approve of young Ruskin poring over his dad’s letters so suggested he keep them away for safekeeping. At end of term when Ruskin Bond went to ask for his letters his teacher was clueless. Now in his eighties forgiving and generous as is his want Ruskin Bond remarks that Mr Priestly probably “meant well” but all that remains of that pile of letters is the one that the young boy spirited away — and still retains all these years later. Looking for Rainbow is a beautiful edition made richer by Mihir Joglekar’s illustrations.

have scheduled a bunch of publications. Puffin India has released Looking for the Rainbow — a memoir he has written for young readers describing the time he spent with his father in Delhi. It was during the second world war. His father was with the Royal Air Force ( RAF), stationed at Delhi. Ruskin Bond’s parents were divorced and his mother was about to get married for the second time. His father decided Ruskin Bond could stay with him for a year in Delhi where he had some rooms rented — at first off Humayun Road and then later nearer to Connaught Place. Ruskin Bond remembers this time spent in Delhi fondly even later when he was sent off to boarding school in Simla. In fact decades later he recalls with a hint of sadness that Mr Priestly, his teacher, did not approve of young Ruskin poring over his dad’s letters so suggested he keep them away for safekeeping. At end of term when Ruskin Bond went to ask for his letters his teacher was clueless. Now in his eighties forgiving and generous as is his want Ruskin Bond remarks that Mr Priestly probably “meant well” but all that remains of that pile of letters is the one that the young boy spirited away — and still retains all these years later. Looking for Rainbow is a beautiful edition made richer by Mihir Joglekar’s illustrations.

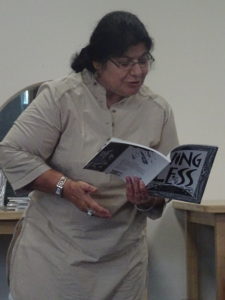

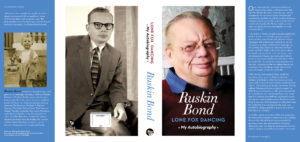

Looking for Rainbow serves as a wonderful introduction and is probably the slim pickings of the larger project memoir Ruskin Bond will eventually publish with Speaking Tiger Books. It is as his publisher, Ravi Singh, told me the longest book Ruskin Bond has ever written — nearly a 100,000 words. It is “hugely readable. Moving, too, in parts.” Lone Fox Dancing is scheduled for June 2017. Earlier this year Scholastic India released a biography of his written by Shamim Padamsee in their Great Lives series.

Looking for Rainbow serves as a wonderful introduction and is probably the slim pickings of the larger project memoir Ruskin Bond will eventually publish with Speaking Tiger Books. It is as his publisher, Ravi Singh, told me the longest book Ruskin Bond has ever written — nearly a 100,000 words. It is “hugely readable. Moving, too, in parts.” Lone Fox Dancing is scheduled for June 2017. Earlier this year Scholastic India released a biography of his written by Shamim Padamsee in their Great Lives series.

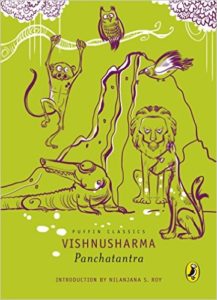

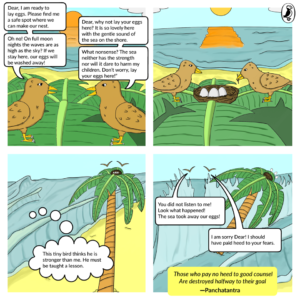

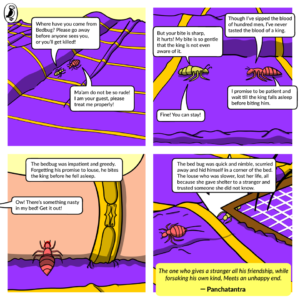

His long-standing publisher, Rupa, with whom Ruskin Bond has a special relationship for decades now has also brought out two volumes of his works. The Wise Parrot is a collection of folktales retold by Ruskin Bond. He says in the introduction:

I may be no Scherazade, and that is a relief, for it would be rather difficult for me to think of stories knowing my head may be chopped off the next day, yet I have found some ancient legends that are as enthralling as hers and presented them here. There are creatures who have lived in our collective imaginations for ages. There are stories of wit and stories of immense stupidity. And in all this, what shines forth is the power of human imagination that has thrived for millions of years. From the first cave paintings, to today’s novels, the thrill of telling a story has never died down. And here’s wishing that it may live long, bringing people, animals, fairies and ghosts to life forever.

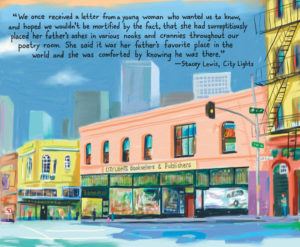

The Elephant and the Cassowary is an anthology of his favourite stories about wild animals and birds and the  jungle. The title story is a perennial favourite and is utterly delightful. A master storyteller and a voracious reader like Ruskin Bond when become a brand name like no other have the luxury of also being tastemakers. As well-known prolific scifi writer and anthologist Isaac Asimov says in his splendid memoir I.Asimov : [An anthology] performs the same function as a collection does, bringing to the reader stories he may be glad to have a chance to read again or stories he may have missed altogether. New readers are able to read the more notable stories of the past.” Another anthology that Ruskin Bond has put together and is being released this week by Viking, an imprint of Penguin, is Confessions of a Book Lover. Both these anthologies between them contain previously published works by writers such as Rudyard Kipling, F.W. Champion, Henry Astebury Leveson, Joseph Conrad, Laurence Sterne, H.G. Wells, William Saroyan, Stacy Aumonier, and J.B. Priestley. Anthologies are a splendid way to discover new material even though some people think otherwise. Ruskin Bond has it right with these two eclectic anthologies. They jump centuries but the underlying principle of a good story is what matters. It is no wonder then to discover the delightful publishing connection between legendary publisher Diana Athill and Ruskin Bond. She gave him his first break as a writer while still at Andre Deutsch. She certainly knew how to spot talent!

jungle. The title story is a perennial favourite and is utterly delightful. A master storyteller and a voracious reader like Ruskin Bond when become a brand name like no other have the luxury of also being tastemakers. As well-known prolific scifi writer and anthologist Isaac Asimov says in his splendid memoir I.Asimov : [An anthology] performs the same function as a collection does, bringing to the reader stories he may be glad to have a chance to read again or stories he may have missed altogether. New readers are able to read the more notable stories of the past.” Another anthology that Ruskin Bond has put together and is being released this week by Viking, an imprint of Penguin, is Confessions of a Book Lover. Both these anthologies between them contain previously published works by writers such as Rudyard Kipling, F.W. Champion, Henry Astebury Leveson, Joseph Conrad, Laurence Sterne, H.G. Wells, William Saroyan, Stacy Aumonier, and J.B. Priestley. Anthologies are a splendid way to discover new material even though some people think otherwise. Ruskin Bond has it right with these two eclectic anthologies. They jump centuries but the underlying principle of a good story is what matters. It is no wonder then to discover the delightful publishing connection between legendary publisher Diana Athill and Ruskin Bond. She gave him his first break as a writer while still at Andre Deutsch. She certainly knew how to spot talent!

Happy birthday, Mr Bond!

17 May 2017